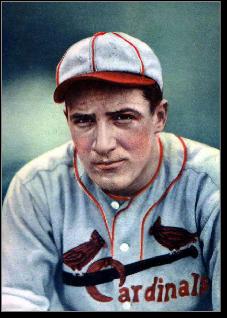

Sport: Baseball

Born: November 24, 1911

Died: March 21, 1975

Town: Carteret, New Jersey

Joseph Michael Medwick was born November 24, 1911, in Carteret, NJ. The son of Hungarian immigrants, Joe was one of four children. During the 1920s, he starred as a football running back for Carteret High, earning All-State honors. He also excelled in baseball, basketball and track. Joe fielded several scholarship offers from major college football programs, but in the early days of the Depression he needed cash on the barrelhead. He agreed to play minor-league ball for the St. Louis Cardinals under an assumed name so that if baseball didn’ t work out, his amateur status would be protected and he could go to college and play football.

Joe began his pro baseball career in the Class-C Middle Atlantic League in 1930. It became immediately apparent that he had a bright future in baseball. That summer, he hit 22 homers in 75 games and batted over .400. After two big seasons with Houston in the Texas League, Joe was considered major league ready. But not before he acquired the nickname “Ducky” for the way he splashed around when he swam. Joe didn’ t like the name—he preferred “Muscles.”

Joe broke into the big leagues at the end of the 1932 season. He batted .349 in a handful of games and won the starting leftfield job for the Cardinals in 1933. In 1934, Joe batted .319 and led the National League in triples. He started for the NL in the All-Star Game and helped the Cardinals win the pennant. Joe collected 11 hits in the World Series against the Tigers as St. Louis won in seven games.

In Game 7, Joe lashed a triple with the Cardinals safely ahead. As he slid into third, a frustrated Marv Owen stomped him with his cleat. Joe responded by planting both of his spikes in Owen’ s chest. The umpires stepped in before a fight occurred, but when Joe took his position in left, Detroit fans pelted him with garbage. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis removed Joe from the game, ostensibly for his own safety. Had it been a regular-season contest, the umpires might have forfeited the game to the Cardinals.

From 1935 to 1937, Joe led the league in total bases each season. He was the NL RBI champ from 1936 through 1938. In 1936, he established a new league record with 64 doubles—a mark that still stands. Joe’ s finest season came in 1937, when he led the NL in hits, runs, doubles, homers, RBIs, batting and slugging. His Triple Crown was the last by an NL player. He also won the MVP that year.

The Cardinals were famously tight-fisted with their stars. After winning the Triple Crown, Joe was paid $20,000 for the following season. He led the NL in RBIs again, but saw his salary cut by 10 percent for 1939. A constant complainer, Joe was beginning to wear out his welcome in St. Louis even though he was arguably the best outfielder in the league. In June of 1940, he was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers.

During Joe’ s first series against his old team, he was hit in the head with a fastball from Bob Bowman. The Dodgers rushed from their dugout—half to check on Joe, who was lying unconscious, and half going after Bowman. Even Dodger GM Larry MacPhail hopped into the field and took a swing at the St. Louis pitcher.

Joe made it back onto the field in time to play in his seventh consecutive All-Star Game. and finished the year with a .301 average. In 1941, Joe was a cornerstone of Brooklyn’ s pennant-winning team. He took special delight in the fact that the Dodgers had edged the Cardinals down the stretch. However, Brooklyn fell to the Yankees in the World Series.

At an age when most players begin thinking about retirement, Joe continued to be a valuable player—in part due to the manpower shortages of wartime baseball. During the war years, he performed for the Dodgers, Giants and Braves, before returning to the Cardinals as a bench player during the 1947 and 1948 seasons. Joe stayed in baseball as a minor-league player-manager from 1948 to 1951.

Under normal circumstances, Joe would have been an instant selection for the Hall of Fame when he became eligible in the mid-1950s. But the young baseball writers he had dismissed and antagonized in the 1930s were now the same people voting on his enshrinement. They made Joe wait until 1968.

Joe often visited the Cardinals during spring training, working as a de facto batting instructor. It was in St. Petersburg in March of 1975 that he was felled by a heart attack during camp. He died a few days later at age 63.