The game of basketball originated at the YMCA Teacher’s College in Springfield, Massachusetts in the winter of 1891–92. Its inventor, James Naismith, had been charged with the task of creating a form of physical activity that would keep students engaged and in shape during the winter months. Prior to that, the indoor “sports” of choice was Indian Clubs and calisthenics; needless to say, something more competitive was needed. By the end of 1893, basketball had begun to spread throughout the country via the network of YMCA gymnasiums, and both men and women were learning the game.

On November 7th, 1896, a team from Brooklyn traveled to the Masonic Temple in Trenton to play a team from that city. An admission fee was collected from spectators and the players on both clubs were paid to play. Thus Trenton became the site of the first professional basketball game. The home club won, 15–1. In 1898, six teams from the same region formed the first pro basketball circuit, which they called the National Basketball League. It lasted five years—longer than most fledgling sports organizations of that era. New Jersey’s first basketball star was Harry Hough (left), a Trenton teenager who created a sensation with his ability to dribble with either hand and make baskets “on the run.” He turned pro at 15 and played at a high level for two decades.

By the early 1900s, most major colleges had started men’s basketball programs. When these players graduated, they often supplemented their working salaries by playing semipro ball for a few dollars on the weekends, or coaching local high-school teams. Much of that talent ended up in New Jersey. In 1915, Ernest Blood was hired to coach the Passaic High School varsity. Blood was an early proponent of the full-court press, fast break and team-oriented passing. His players executed these strategies so well that Passaic High lost only one game during the coach’s reign. At one point, the school won 159 games in a row. By then, Blood had already left the Hilltoppers to coach St. Benedict’s Prep in Newark. Among the early New Jersey players who made a living playing basketball were Tom Barlow and Stretch Meehan.

One of the key contributors to the growth of basketball in the Garden State was the expansion of railroads between 1900 and 1920. Hundreds of towns had depots and many of those towns installed trolley lines to make access to train travel easier. This enabled basketball fans to get to games quickly and cheaply—swelling crowds and revenues—and also enabled the top players to perform for multiple teams. The government began shifting subsidies from rails to paved highways in the 1920s, but this only increased the transportation options for fans and players.

During the 1930s and ’40s, New Jersey was the home to more than a dozen teams in the American Basketball League. Another league called the ABL had flourished briefly in the 1920s, with teams all over the country, but it failed in 1931. The “new” ABL was concentrated in the northeast. The league played its games on weekends and the teams were backed by local stores or businesses. These early pros played games primarily on the weekends, usually in dance halls or armories. On a Friday or Saturday night, a ticket to an ABL game entitled the purchaser to stay afterwards and enjoy live music after the baskets were cleared away. The cities represented in the ABL included Atlantic City, Camden, Elizabeth, Hoboken, Jersey City, Newark, North Bergen, Passaic, Paterson, Trenton and Union City. Ironically, the Brooklyn Jewels probably boasted two of New Jersey’s top pros, Honey Russell and Matty Begovich (right).

The most successful New Jersey franchise in the 1930s was the Jersey Reds, who played in the neighboring towns of North Bergen and Union City. Their stars included Moe Spahn, an All-American for City College in the early 1930s and Hook Andersen, an All-American for the undefeated 1933–34 NYU Violets. In the 1940s, the Trenton Tigers were one of the better teams in the ABL. They finished first in the regular season in 1942–43 and won the ABL title in 1946–47.

Although the ABL boasted some major talent, it was never regarded as a “major” league. Starting in 1937, it competed for players with the National Basketball League—and the NBL usually won out. NBL teams were supported by large companies in the Midwest, which could offer weekday jobs to its players as an incentive to sign. This was a big incentive during the Great Depression, when the jobless rate in America was close to 30%. Eventually, the NBL merged with a league called the Basketball Association of America and became the NBA.

During the 1940s, New Jersey’s best basketball team—at any level—was Honey Russell’s Seton Hall Pirates. The team went undefeated in 1939–40 and lost a total of only seven games over the next three season, before World War II suspended the school’s program for three years. Bob Davies was the star of the team in the early ’40s and coached the team to a 24–3 record in 1946–47.

Big-time basketball returned to New Jersey in the late-1950s with the advent of the Eastern Professional Basketball League. The Eastern League served as an alternative to the NBA for many talented players. The salaries were lower than the NBA, but because league games were played on the weekends, players could put their college degrees to work and jump-start their careers outside of basketball. Eastern League teams represented the cities of Camden, Trenton, Cherry Hill, Asbury Park, East Orange, and Hamilton. The level of competition was good; some Eastern League players were clearly better than their NBA counterparts—in no small part because it welcomed African-American players who were denied roster spots in the NBA because of an unwritten “quota” system.

When the Warriors left Philadelphia for San Francisco in 1962, their veteran star, Paul Arizin (left), decided to stay in the area instead of heading west. He played for the Camden Bullets and was named MVP and Rookie of the Year in his first season. The Bullets beat the Trenton Colonials for the EBL title the following spring. Among the top New Jersey-born players in the league was Cleo Hill, a sensational talent who was denied an opportunity to play in the NBA. The Eastern League eventually morphed into the Continental Basketball Association.

The first true “major league” hoops team in the Garden State arrived in 1967 in the form of the New Jersey Americans. The Americans began life as the New York City entry into the newly formed American Basketball Association. Pressure from the NBA Knicks made it impossible for owner Arthur Brown to find a home in the Big Apple, so with the ABA’s inaugural season fast approaching, he settled for the Teaneck Armory.

Led by high-scoring Lavern Tart, the Americans finished their first season tied for fourth place with the Kentucky Colonels. The ABA scheduled a one-game playoff to determine which of the two teams would play the Minnesota Muskies in the opening round of the playoffs. The game was scheduled to be held in Teaneck, but the circus was in town so another location had to be found. Brown settled on the Commack Arena in Long Island. A court was hastily assembled over the hockey rink that served as home ice for the minor-league Long Island Ducks. The court was deemed unplayable and the Americans forfeited the game, thus missing the playoffs. The following season Brown, renamed the club the Nets and finally negotiated a New York venue for them to call home—the Commack Arena!

The 1960s and 1970s provided lots of college highlights for New Jersey basketball fans. Bill Bradley (right) of Princeton was an All-American in each of his three varsity seasons, starting in 1962–63. He led the Tigers to the Final Four in 1965. Other Princeton stars of the 1960s and ’70s included Geoff Petrie and Brian Taylor. Both played for coach Pete Carril, who led the Tigers for three decades and devised the Princeton Offense, a ball-control system that featured a whirl of picks, screens and backdoor layups. A year after Carril passed away, his legacy was on display in the 2023 NCAA Tournament, when the Tigers reached the Sweet 16 for the first time since 1967. Rutgers basketball also enjoyed a nice run in the 1970s, reaching the Final Four in 1976.

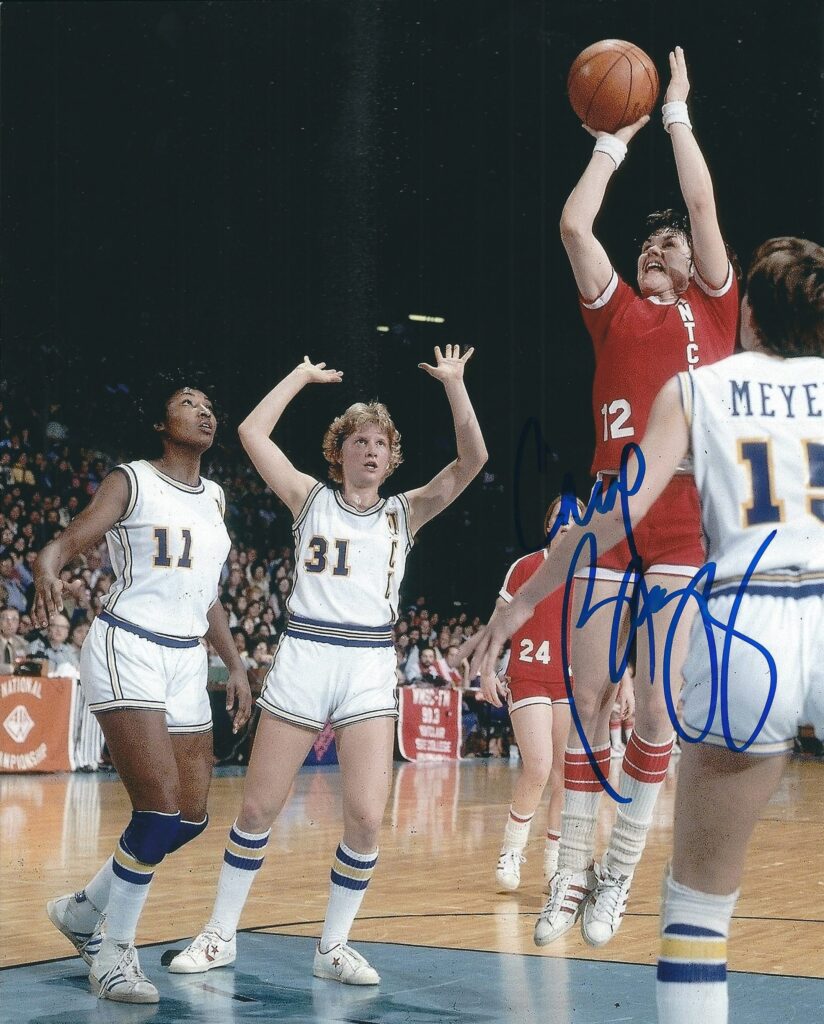

The biggest basketball star in New Jersey during the 1970s—and perhaps ever— was Carol Blazejowski (left). She electrified fans first as a prep sensation at Cranford High and then as the star of the Montclair State women’s team. “Blaze” had an impeccable court IQ, an accurate jumpshot and a slashing style that made her almost impossible to stop. A 30-point game was considered a disappointment for Blazejowski; she once netted 52 against Queens College to set a record for points scored in Madison Square Garden. It stood until Michael Jordan topped it with 55. In 1978, she won the first Wade Award as the top player in women’s college basketball.

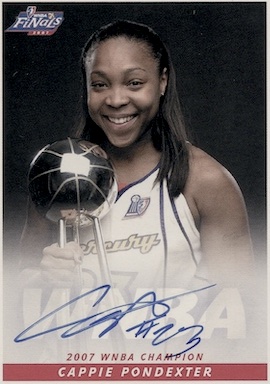

New Jersey women’s basketball continued to gain momentum in the years that followed. In the late-1980s, the Rutgers program got a huge boost from Sue Wicks, a 6’3” forward who was named national Player of the Year as a senior in 1988. Her coach, Theresa Grentz, spent nearly two decades on the sidelines for Rutgers and established a program that was further elevated by Vivian Stringer, who guided her team to the Final Four in 2007. Stringer’s best player was Cappie Pondexter, who was the last New Jersey college player to earn first-team All-America honors, in 2006.

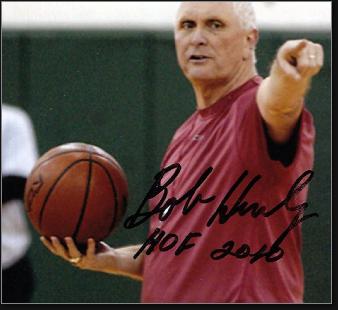

Another trailblazing coach in New Jersey basketball was Bob Hurley (right). He started his coaching career at St. Anthony’s High School in Jersey City and, in 2011, won his 1,000th game. He led the school to 26 state championships, more than any high school in the country. His 1989 team featured three future first-round NBA picks: Terry Dehere, Rodrick Rhodes and his son, Bobby. Hurley became just the third high-school coach to be inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Pro hoops returned to New Jersey in 1977, one year after the ABA merged with the NBA, when the Nets relocated to the Garden State. When the Nets joined the NBA, the team featured Julius Erving and had just signed Tiny Archibald. But Erving had to be sold in order to afford the entry cost and Archibald suffered a devastating injury. The club moved to New Jersey for the 1977–78 season, playing in Rutgers’ Piscataway arena until a new home in the Meadowlands complex was completed.

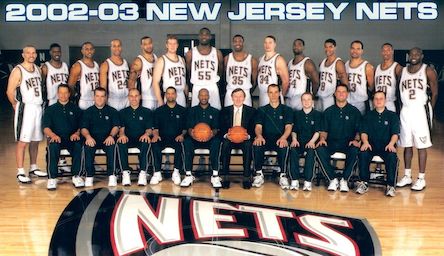

The Nets developed some All-Star players after moving back across the Hudson, including Bernard King, Buck Williams and Derrick Coleman. But not until the new century did they have a serious championship contender. In 2001–02 and again a season later, the Nets won their division and advanced to the NBA Finals. They lost both times, first to the Lakers and then to the Spurs. The team was led by the “big three” of Jason Kidd, Kenyon Martin and Richard Jefferson. In 2005, the Nets announced plans to move to Brooklyn as soon as an arena was completed as part of the Atlantic Yards complex. In 2009, the Nets were purchased by Russian financier Mikhail Prokorov. He also invested in the Brooklyn development. The team took up residence in Brooklyn’s Barclays Center in 2012–13.

New Jersey First-Team All-Americans

Arthur Loeb (Princeton) 1922

Carl Loeb (Princeton) 1926

Ken Fairman (Princeton) 1933

Bob Davies (Seton Hall) 1942

Walter Dukes (Seton Hall) 1953

Bill Bradley (Princeton) 1963-65

Bob Lloyd (Rutgers) 1967

Phil Sellers (Rutgers) 1975-76

Terry Dehere (Seton Hall) 1993

Cappie Pondexter (Rutgers) 2006