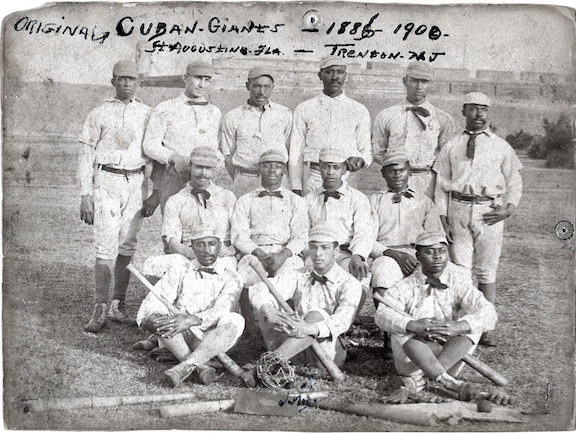

During the 1880s, when the color line was being drawn in organized baseball, several African-American teams formed to barnstorm in the Northeast and Midwest. The best of these teams was the Cuban Giants, who made Trenton their base of operations in the late-1880s. The team’s name was a wink to the politics of race at the time—because Cuba was part of the Spanish empire, black players of Cuban descent were regarded by white audiences as being superior in some way black Americans. There were no actual Cubans on these teams, of course. Trenton’s “Cubes” claimed the distinction of being the first all-salaried African-American baseball team. Their star catcher was Clarence Williams.

Baseball was a popular spectator sport among visitors to Oceanside resorts. From the 1880s into the 1920s, it was not unusual for a resort’s African-American employees to play for the amusement of guests, particularly at properties along the Jersey Shore. Often, the opponent would be a black barnstorming team. In 1916, with Atlantic City booming, two African-American politicians—Tom Jackson and Henry Tucker—purchased a Florida club called the Duval Giants and moved them north. They renamed the team the Bacharach Giants in honor of Atlantic City mayor Harry Bacharach.

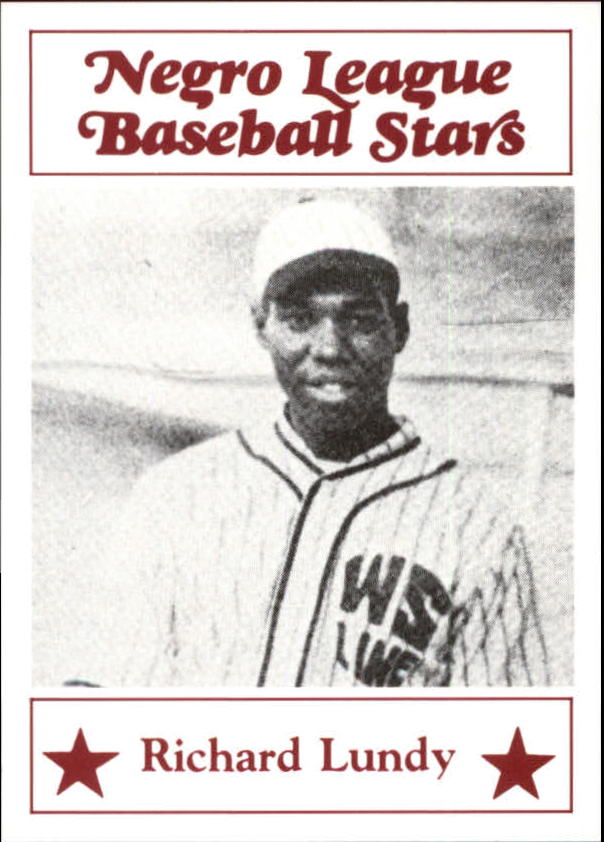

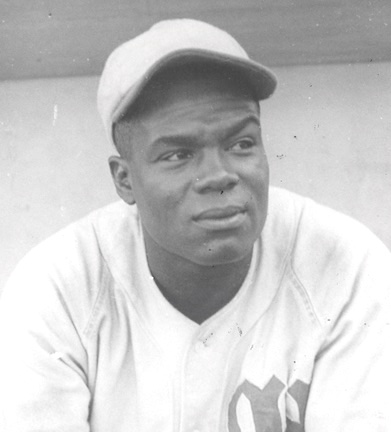

The Bacharach Giants traveled the country playing both black and white clubs. They joined the Eastern Colored League in 1923 and won pennants in 1926 and 1927. They lost to Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants in the Negro World Series both years. Among the superstars who suited up for the club were shortstop Dick Lundy (left), who earned effusive praise from white opponents the team played, pitcher Cannonball Dick Redding, who pioneered the “hesitation pitch” later perfected by Satchel Paige, and legendary player-manager John Henry Lloyd and outfielder Fats Jenkins, better known as the point guard and captain of the Harlem Rens basketball team.

In 1922, a player with New Jersey roots, Charlie Culver, signed with the Montreal Royals of the newly formed Class-B Eastern Canada League—effectively “breaking” organized baseball’s color barrier a generation before Jackie Robinson. Culver, who had played with the Red Caps (a team made up of African-American employees of New York’s Penn Station) prior to moving north, only lasted a week with the Montreal club. It turned out he had signed a contract with a Canadian semipro team weeks earlier and that contract was enforced, ending what could have been a history-making season.

The 1930s saw the formation of two successful black baseball circuits, the Negro National League and Negro American League. Despite the economic despair of the Depression, the shifting demographics of America enabled these leagues to survive. Their teams barnstormed around the country, providing cheap entertainment to small-town fans both black and white, and met for big games in big-league stadiums when the white teams were on the road. The Great Migration had created a concentration of working-class African-Americans in the northern cities that anchored the leagues. League winners met in an annual championship series, and played popular All-Star games.

Black baseball thrived in New Jersey during the 1930s, with two different clubs calling Paterson’s Hinchcliffe Stadium home: the New York Black Yankees and New York Cubans. The Black Yankees played in Paterson as both an independent club and as a member of the Negro National League, starting in 1934. The Cubans, who used the Polo Grounds when the Giants were away, were Hinchliffe tenants in 1935 and 1936. The cubans were led by player-manager Martin Dihigo, who many historians consider the greatest all-around player of his era. Dihigo’s stars included Lundy, Luis Tiant Sr. and Alejandro Oms.

Upper Case Collection

In 1936, Abe and Effa Manley purchased the Newark Dodgers and merged them with the Brooklyn Eagles to create the Newark Eagles. The 1936 roster included future Hall of Famers Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, Mule Suttles and Willie Wells. Suttles had broken in to pro ball 15 years earlier, with the Bacharach Giants and became a Newark cultural icon. The Eagles shared Ruppert Stadium with the Newark Bears, but were generally acknowledged by local sports fans as the superior club. Over the next decade, the Eagles put more great stars on the field, including Jimmy Crutchfield, Buster Brown, Max Manning, Biz Mackey, Lennie Pearson (right), Monte Irvin, Don Newcombe and Larry Doby. Doby was discovered by the Eagles playing ball for Eastside High in Hinchliffe Stadium. Dick Lundy became the team’s longtime manager.

In 1946, Newark won the NNL pennant and went on to beat the Kansas City Monarchs in a 7-game World Series. Ironically, the team went into decline at the height of its power after the majors integrated. The Eagles lost their best players with no compensation, as major-league clubs did not respect their contracts. The Manleys sold to owners who moved the team to Houston and the league folded in 1948.

In the 21st century, researchers and historians began revisiting and preserving the Garden State’s “black ball” heritage with renewed vigor. The trigger was Larry Doby’s enshrinement in Cooperstown in 1998, and the publicity surrounding this honor. Doby’s passing in 2003 pushed that conversation forward. In 2006, Effa Manley was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2008, McFarland published a book by Alfred Martin entitled The Negro Leagues: A History. In 2014, Hinchcliffe Stadium received National Landmark designation. It marked the first time a venue exclusively built for baseball received this honor. It also happens to be the last place in the tri-state area still standing where Negro League games were played.