Sport: Boxing

Born: October 22, 1895

Died: May 1, 1969

Town: West Orange

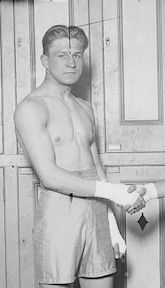

Karoly Weinsachzyowski was born October 22, 1895 in Budapest, Hungary and grew up in West Orange, NJ. The family emigrated from the Austro-Hungarian Empire when he was a baby and Americanized their name to Weinert. Karoly became Charley. Tall, tough and coordinated, Charley was drawn to boxing as a boy and began training with Percy Woodruff, a local boxing manager whose connections with local fight promoters promised a quick path to prominence.

Charley turned pro a few months after his 15th birthday and faced Dutch Monroe at the Central Institute in Newark in January 1911. That match was a draw, but beginning that May, he fought 30 times without a loss. In December 1913, Charley scored a pair of impressive wins against light heavyweights Battling Levinsky in New York City and Tommy Madden in Newark. After dismantling Madden, Charley was hailed as the next “Great White Hope” who might have a shot at Jack Johnson’s title. At 18, he weighed only 160 pounds at the time but seemed headed toward heavyweight status. His combination of elegant footwork, defense and punching power drew comparisons to Jim Corbett at the same age.

A natural righty, Charley could punch with equal power with both hands, using a quick left jab and left hook to supplement a strong, accurate right uppercut. As his career progressed, opponents often prepared more for his left-handed punches than his right-handed ones. His most significant weakness was his tendency to get bored and careless when an opponent simply chose to cover up. Often he would drop his gloves, creating an inviting target for a counterattack. Charley wasn’t a big fan of rigorous training, either, and could often be seen out partying in the days before a bout.

In the spring of 1914, Charley and his manager had a falling out, but they continued to communicate. In October, Woodruff got Charley a bout with Jim Savage, a hard-punching veteran with ring experience against several heavyweight contenders. Prior to the bout, Woodruff told Charley that he had arranged the match with the understanding that the two men would fight to a draw. When Charley learned that Savage had not been aware of this deal, he became furious about the double-cross, pulled out of the fight, and reported his former manager. The incident was covered by the New York Times under the headline “Boxing Scandal Over in Jersey.” Earlier that year, Charley’s prowess had been trumpeted by the same paper in the January 30th headline “New Boxing Star Looms Up in Ring.”

The two boxers would eventually meet—in 1915 and 1916—and Charley would win both fights.

Charley’s undefeated streak came to an end in November 1914, when light heavyweight Jack Dillon scored a technical knockout at the Olympia AC in Philadelphia. Dillon beat Charley again a year later in a 10-round decision at the old Madison Square Garden on 26th Street in Manhattan. In the second fight, Charley came out like a hurricane, winning the first four rounds. But Dillon waited for an opening and scored several heavy blows in the fifth—then carried the fight the rest of the way.

This would be the script for many of Charley’s subsequent fights. Dubbed “The Newark Adonis,” he looked fantastic early in fights against equal or lesser opponents, which was usually enough to win. But against better fighters, he struggled to finish. In 98 bouts between 1911 and 1929, he scored impressive victories over Gunboat Smith and Jack Sharkey, but lost to the top heavyweights and light heavyweights of his era, including Harry Greb, Jim Flynn, Harry Wills, Luis Firpo and Gene Tunney.

In 1920, the Newark Sportsmen Club offered to put up a $50,000 guarantee if then-champion Georges Carpentier fought Charley in New Jersey. This was as close to a title shot as the Newark Adonis would get. The French heavyweight instead took a fight with Jack Dempsey, who knocked him out in Jersey City, and Charley never got a shot at Jack Dempsey—although he was considered a Top 5 contender into the mid-1920s. Charley left the ring in his 30s with a record of 73–17–8 with 27 knockouts.

Charley lived and worked in New Jersey the rest of his life. During the 1950s, he ran a branch of the Newark Public Library. Charley passed away at the age of 73. In 1970, the year after his death, he was enshrined in the New Jersey Boxing Hall of Fame.