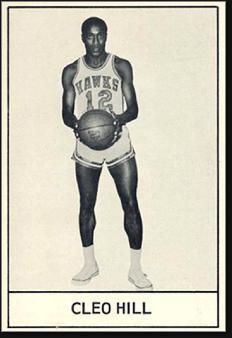

Sport: Basketball

Born: May 24, 1938

Died: August 10, 2015

Town: Newark, New Jersey

Cleo Hill was born May 24, 1938 in Newark, NJ. A good student and gifted athlete, he gravitated toward the city’s basketball courts in the early 1950s, and became a Brick City legend by his early teens. Cleo attended South Side High (now Malcolm X Shabbaz High), where he quickly became the star of the Bulldogs varsity.

Cleo could score with either hand and had a full arsenal of jumpers, hooks and two-handed set shots. Though he stood only 6’1”, he had a vertical leap of nearly four feet and was one of the first high-schoolers to play above the rim. At the time, 7-footer Wilt Chamberlain was known for being able to take off and dunk from the free throw line; Cleo, a foot shorter, also had this talent. Al Attles of Weequahic High said Cleo was the best player he faced in school or on the playground.

During the 1950s, the vast majority of major college basketball programs did not offer scholarships to African Americans. However, Cleo found a willing taker for his talents in the person of Clarence “Big House” Gaines at Winston-Salem Teachers College (now Winston-Salem State) in North Carolina, a historically black school where most of the students were female. Cleo consistently scored over 20 points a game as a collegian, and average close to 30 as a senior in 1960–61.

Billy Packer, a guard on the ACC champion Wake Forest Demon Deacons in 1961 and 1962, became friendly with Cleo and the two teams occasionally scrimmaged on Sunday mornings. The Wake players were unable to stop him. Several years later, Earl Monroe starred for the Rams. Fans who saw them both play were nearly unanimous when asked which player was better as a collegian: Cleo.

In the 1961 NBA Draft, the St. Louis Hawks selected Cleo with the 8th pick, making him the league’s first first-rounder from a predominantly African-American school. Cleo stunned his St. Louis teammates in preseason scrimmages—including future Hall of Famers Clyde Lovelette, Bob Pettit and Cliff Hagan. Against the best in the business, he was unstoppable. In his NBA debut, Cleo netted 26 points.

Although the NBA was beginning to feature African-American scoring stars like Chamberlain, Oscar Robertson and Elgin Baylor, St. Louis wasn’t quite ready for a player like Cleo. The Hawks were scheduled to play the Celtics in an exhibition game in Louisville, and controversy erupted when Bill Russell was refused service at his team’s hotel. Russell convinced the African-American players on both teams to boycott the game. The Celtics’ owner supported his players but Hawks owner Ben Kerner did not. He traded away Sihugo Green and Woody Sauldsberry and ordered coach Paul Seymour to bench Cleo. When Seymour refused, he was fired. Seymour later told Cleo that he wouldn’t have been able to look himself in the mirror if he had followed orders.

New coach Harry Gallatin did as Kerner demanded and Cleo languished on the bench. He ended up averaging just 18 minutes a game, and when he was on the court his teammates froze him out. The aging white stars were not interested in watching him outscore them. When Cleo encountered the same situation at the start of the 1962–63 season, he sulked and was cut by the Hawks. Other NBA teams, believing he might create similar problems on the court or in the locker room, showed no interest in signing him.

Cleo continued his pro career in the ill-fated American Basketball League with the Washington Tapers. The league folded midway through the season, but for that half-year, Washington fans got to see Cleo and Sylvester Blue—an equally amazing talent—on the same court together. Cleo continued his pro career in the Eastern League, a minor-league circuit with major talent. Eastern League clubs played on the weekends, enabling players to work jobs during the week. Many EL players made more annually than NBA players. This included Cleo, whose college education enabled him to find regular work as a substitute teacher. He starred for the Trenton Colonials, New Haven Elms and Scranton Miners before calling it a career at age 30 in 1968.

Cleo went into coaching and found a home back in his hometown, leading the Essex County College hoops squad to 489 wins. After 24 years with the Wolverines, he took a job coaching the varsity at Newark Vocational High School. In 2008, Cleo was “rediscovered” by basketball fans (and his own astonished players) when he was one of the stars featured in the documentary Black Magic, produced by Earl Monroe. Cleo passed away in 2015 at the age of 77.