Sport: Baseball

Born: July 28, 1867

Died: August 31, 1910

Town: Salem, New Jersey

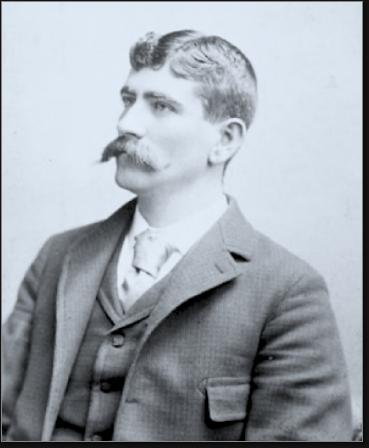

Charles H. Esbacher was born July 28, 1867 in Salem, NJ. A left-handed pitcher who threw from various angles and could change speed, spin and location, Charley Esbacher reinvented himself as “Duke Esper” when he began to hone his craft on the semipro ballfields in South Jersey and around Philadelphia. Duke was an ironworker who suffered from an irregular heartbeat, so he suspected his life might be short. When he was offered a chance in 1889 to pitch professionally in the Delaware League he jumped at the chance.

Duke’s slow, tantalizingly deliveries were effective enough to earn him a spot as an extra arm with the Philadelphia Athletics in 1890. He pitched well early but faded over the summer—as did the Athletics. The team released Duke and, after pitching a couple of games for the Pittsburgh Alleghenys, he returned to Philadelphia as a member of the Phillies—and was a perfect 5–0 down the stretch. When the dust settled on his rookie campaign, Duke was 13–11.

The following season, Duke won 20 games for the Phillies, astounding fans who were aware of his well-publicized bad ticker. Three of those wins came in head-to-head battles with the great Cy Young in a match-up of the National League’s softest tosser and hardest thrower. The Phillies made sure to pitch Esper whenever Young was on the mound. His career record against the Hall of Famer was 7–7.

Despite Duke’s heroics—and a 13–6 record midway through the 1892 season—the Phillies released him and he finished the year with Pittsburgh. He returned to Philadelphia over the winter, where he tended bar and kept patrons amused with his tales of life in the big leagues.

In 1893, Dukee signed to play with the Washington Senators, a dreadful club with a terrible defense. He pitched his heart out (almost literally), enduring 334 innings on the mound and going 12–28. Duke was unhappy in Washington and made it well known. The Senators traded him to the Baltimore Orioles during the summer of 1894 and, with a reduced work load and a better team behind him, he won 10 of his 12 decisions down the stretch to help the O’s win their first pennant. Duke fit right in with Baltimore over-the-top rowdies and was given the honor of starting Game 1 of the Temple Cup against the second-place Giants—which he lost to Amos Rusie.

Duke pitched well for Baltimore in 1895 and 1896, going a combined 24–17 and contributing to two more pennants. His sinker and change-up bedeviled enemy hitters. By the conclusion of 1896, his stamina was so poor that the team didn’t bother to pitch him in the final month. In 1897, the Milwaukee Brewers—a minor-league club—made a deal with Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon to buy Duke for $1,000.

The Orioles never cashed the check and instead sent Duke to St. Louis Browns, who claimed he had not passed through proper waivers. The busted transaction came at the expense of the new Milwaukee manager, a former catcher named Connie Mack.

The Browns were a trainwreck, going 29–102. Duke was the only lefty on the staff, and completed 7 of his 8 starts but won only once. He was so out of shape that the team suspended him. The Browns were bad again in 1898, winning 39 and losing 111 in the NL’s expanded schedule. Duke went 3–5 for the team in what would be his final big-league season. He was released in July.

Duke spent several years as a Philadelphia policeman and also ran a restaurant. He died at 45—not of a bad heart, but of a bad liver. His lifetime record of 101–100 seems a reflection of mediocrity, but there was nothing mediocre about his pitching. When Duke was on, few lefties were better. When he wasn’t, few were worse.