Sport: Baseball

Born: November 7, 1857

Died: May 18, 1913

Town: Paterson, New Jersey

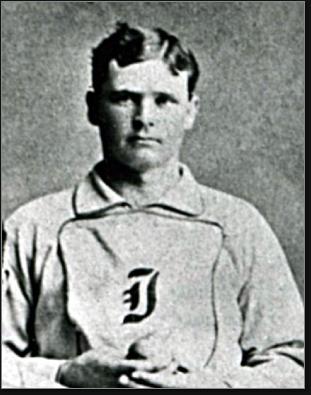

Edward Sylvester Nolan was born November 7, 1857 in Ontario, Canada (possibly the town of Trenton) and grew up in Paterson, NJ. Eddie was part of an active baseball scene in Paterson, which drew talent from the city’s many factories. He was a running-mate of future Hall of Famer King Kelly, cricket star Blondie Purcell and Jim McCormick, who is considered by many to be the most accomplished pitcher not in the Hall of Fame. All four were members of the city’s top amateur club, the Olympics. Eddie stood 5’8” and had a muscular build. He could hurl a baseball with tremendous force, whipping the ball underhand, as the rules of the day dictated.

Eddie signed a professional contract with the Columbus Buckeyes at the age of 17 and was their best pitcher at 18, in 1876. In 1877, he signed to play with the Indianapolis Blues, who were members of the League Alliance. The Alliance was a loose group of minor-league clubs with a talent level perhaps a notch below the International Association and National League, which had just completed its first season. In a March exhibition game in New Orleans, Eddie pitched six hitless innings without the opposing team managing as much as a foul ball. It was a sign of things to come.

Eddie’s 1877 season was nothing short of epic. He pitched in 76 complete games and went 64–4 with 8 ties—racking up the most wins ever in organized professional baseball. Of those 64 victories, 30 came by shutout—including two against the Syracuse Stars on the same day. He allowed 38 earned runs (131 runs in all) with an ERA for the year of 0.50. As was the custom of the day, Eddie earned the title of “The Only” Nolan—reserved for public figures who outshone all others with the same name. His boyhood friend, Mike Kelly, would be known alternatively as “King”·Kelly and “The Only” Kelly.

The Blues were invited to join the NL in 1878. By then, however, Eddie’s arm was shot. He went 13–22 for a poor-hitting team that finished in fifth pace and went out of business owing its players money at the end of the year. Before they did, the Blues suspended Eddie for insubordunation.

At this time, the NL had imposed a rule that any club picking up a banned or suspended player would not be allowed to play exhibitions against league teams. Not only that, but any other club that played the team with the blackballed player would also be prevented from playing exhibitions against NL foes. These games were crucial for the health and welfare of baseball—not just for the minor-league team, but for the National Leaguers, who collected the lion’s share of the gate receipts.

This draconian rule, which was initially installed to enforce discipline, blew up in the face of the National League after Eddie headed west and played for the San Francisco Knickerbockers in 1879. Following the season, the Chicago White Stockings booked an ambitious tour of California only to find out that because all of the teams in the California League had played the Knickerbockers, not a sigle one was allowed to meet the White Stockings!

The NL quickly “reinstated” Eddie.

Eddie pitched for San Francisco again in 1880 and then returned to the NL with Cleveland in 1881 and went 8–14. Eddie played for Pittsburgh of the American Association in 1883 and was winless in seven decisions. He pitched briefly in the short-lived Union Association in 1884 and for the Phillies back in the NL in 1885. His final year as a pro was 1886, his final appearance as a member of Jersey City’s Eastern League club.

Done as a player at 28, Eddie returned to Paterson and joined the police force. He served for more than a quarter-century. He died in 1913, possibly as a result of a stroke or heart attack, or perhaps some internal injury, suffered during the Paterson Silk Strike.