Sport: Basketball

Born: June 1, 1883

Died: April 20, 1935

Town: Trenton, New Jersey

Harry Douglass Hough was born June 1, 1883 in Trenton, NJ. Quick, small and competitive, he took to the sport of basketball in a big way as soon as it arrived in Trenton during the 1890s. “Houghie” studied the rules of the game as a boy and practiced dribbling and shooting with both hands—skills that by no means came naturally to athletes of this era—many of whom regarded basketball as a slightly less-lethal indoor version of football. By the time Harry turned 15, he had perfected the art of “caging the ball on the run,” which is how contemporaries described a layup. At the age of 16, he was playing for pay as a high-energy, high-scoring 5’7” forward.

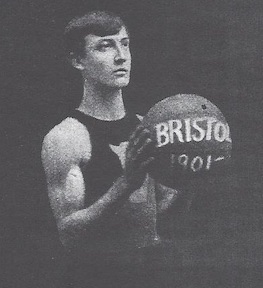

Harry’s first pro team was the Trenton Croziers, an independent club that took the court in 1899–00. In those days, players were typically compensated by passing the hat, or dividing a pre-arranged portion of game receipts. The following winter, Harry crossed the river to play for the Bristol Pile Drivers. One of the team’s coaches was Fred Cooper, a star soccer player who had introduced the concept of sophisticated passing to basketball some years earlier. Harry helped Bristol win a league title in 1902 while still a teenager. Among his teammates were John Plant, who would serve as Athletic Director for the Peddie School.

Within a few years, Harry was being hailed as the best all-around player in basketball. And there is little doubt that he was. Left open, he was an accurate shooter. Guarded chest-to-chest, he could slip around an opponent and create his own shot. There was no point in fouling Harry, for he was a deadly free-throw shooter. It was a rare game in which he failed to score in double-figures.

The extensive rail service in the East during this era made getting from Trenton to New England, upstate New York and Western Pennsylvania fairly simple. Consequently, Harry offered his services to the best and highest-paying pro teams within a day’s travel, including clubs in Massachusetts. In 1904–05, he teamed with another early star, Joe Fogarty, to win the New England League pennant for Natick. The following, season, the two stars took their game to Pennsylvania, where they represented the amusement-starved mining town of Tamaqua. All the while, he maintained a job as a postal worker in Trenton.

Thanks in no small part to Harry’s drawing power, the professional game was spreading west in the early 1900s. Fans who supported the early pro football teams of that era were apparently willing to pay their way to see indoor sports once the weather turned nasty. The Pittsburgh South Side Club paid Harry $300 a month to play for them, making him the highest paid basketball player in the world. He also served as the head coach at the University of Pittsburgh basketball team in 1907–08, while also taking chemistry classes at the school.

From 1908 to 1911, Harry played the Pittsburgh and Trenton teams off each other in what amounted to a talent auction. In 1909–10, he averaged 20 points a game for Trenton—often outscoring entire Eastern League opponents—and led the team to the championship. In 1910–11, influential supporters of the South Side Club successfully arranged through the Postmaster General in Washington for Harry to take a five-month leave of absence from his duties in Trenton and paid him $1,800 in advance to make Pittsburgh his home base. Back in Trenton for the 1911–12 season, he won another league title, along with his third straight scoring championship. The defensive stopper on the Tigers was Fred Gieg, a former ALl-American football player from Millville. That year Harry also coached the Princeton basketball team.

Harry continued playing at a high level into his 30s and was a headline-maker wherever he appeared. He was a taskmaster as a coach and teammate, and a nightmare for referees, arguing every close call. In 1916–17, with his career winding down, Harry played for Germantown alongside a 20-year-old center named Nat Holman. The following year, he played for Frank Bruggy’s team in Scranton, and then retired.

Harry worked as a stockbroker after his playing days and passed away following an operation at the age of 51 in Trenton. In the 1920s, Frank Morganweck, the dean of New Jersey basketball’s early pro days, picked him as the forward on his all-time team. Harry, he said, had everything: “color, speed and a pair of eyes that always found the basket.”