Sports: Football & Hockey

Born: January 15, 1892

Died: December 21, 1918

Town: Princeton, New Jersey

Hobart Amory Hare Baker was born January 15, 1892 in Bala Cynwyd, PA. “Hobey” and his older brother, Thornton, grew up comfortable though not wealthy. Their father, a Philadelphia upholstery manufacturer, Bobby Baker, had been a halfback for the Princeton football team in the 1880s and—with his brother—helped pioneer the notorious Flying Wedge.

Daring, reckless and athletic, Hobey developed a love of organized sports after being sent to the St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire at age 11. Though younger and smaller than his classmates, he tackled boys twice his size on the football field. Hobey demonstrated catlike quickness and agility and was obsessive about physical training. At the age of 15, he was voted the school’s best all-around athlete for the first time.

Above all sports, St. Paul’s was known for hockey. Hobey became the star of the school team at 14. He often practiced alone at night so he could perfect his stickhandling without seeing the puck. St. Paul’s played the nation’s top college teams and often beat them. The year Princeton won the intercollegiate championship, the Tigers lost to Hobey and his teammates 4–0. When St. Paul’s played Harvard, Hobey completely outplayed captain Clarence Pell, who was considered the fastest skater in college hockey at the time. The greater sports world first discovered Hobey when he skated rings around the top American hockey club, St. Nick’s of New York City, at the age of 16.

Rumors began swirling that Hobey was planning to attend Yale. That triggered a large contingent from Princeton to travel to St. Paul’s and they convinced him otherwise.

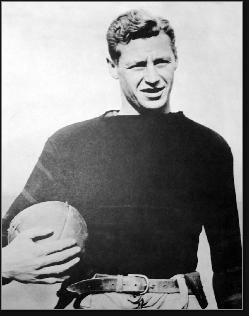

Hobey stood 5’9”, weighed a shade over 160 pounds, and could run the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds. As a Princeton freshman, he was recruited by almost every coach on campus, including the swimming team and track teams. The first time Hobey picked up a rifle, he shot well enough to make the Princeton varsity. He jumped on a horse at nearby Meadowbrook and mastered the finer points of polo in an afternoon. He was a talented golfer and tennis player, despite having little experience or interest in those sports. Hobey was considered to be the best outfielder on campus, but Princeton had a rule limiting students to two varsity sports, and Hobey picked the two roughest—football and hockey. He chose to wear no padding whatsoever in either sport, save for a pair of lightweight hockey gloves.

Hobey’s speed, strength, coordination, boundless energy and peripheral vision served him well on the ice and gridiron. But it was his relentless will to win and amazing discipline that elevated those around him.

As a sophomore in 1911, Hobey led the Tigers to the national football championship. He and Sanford White starred in the season-ending victory over Yale. As a junior in 1912, Hobey unveiled his trademark play. In an era when teams punted 20 or more times a game to jockey for field position—often on first down—Hobey specialized in timing his catches so he could take the ball on a full gallop and tear through the coverage for healthy gains. His return yards regularly dwarfed Princeton’s yards from scrimmage. In three varsity seasons, Hobey crossed the goal line 18 times. Although Princeton did not repeat as champions in 1912, Hobey was named an All-American halfback, along with Jim Thorpe.

As a senior in 1913, Hobey had another stellar season serving as captain of the squad. In his final college game, against Yale, he made a 44-yard drop-kick from an impossible angle to tie the game 3–3, and then made a game–saving tackle to preserve the tie.

Hobey’s hockey career at Princeton got off to a frustrating start. While he played on the freshman football team, the school did not have a freshman hockey team, and Princeton would not allow him to play with St. Nick’s in New York. Once Hobey got on the ice for the varsity in 1911–12, he was a revelation. He score six goals in his first game, against Williams. The Tigers won the intercollegiate championship each year he laced up his skates for the varsity.

As in football, Hobey drew unprecedented crowds to his hockey games, both home and away. During the 1913–14 season, Princeton played Harvard in the Boston Arena, with more than 6,000 fans crammed into the building and tickets selling for many times more their face value. Princeton won 2–1 in triple-overtime.

In these formative years, forward passing was forbidden in hockey. Most teams set up elaborate, swirling plays featuring tricky drop passes to free a shooter. Hobey played it differently. He would pick up a loose puck in his end, skate once or sometimes twice around his own net to pick up speed and then power into the attacking zone. From all those nights at St. Paul’s, he was able to maneuver without glancing down at the puck; it looked like a magnet on his stick. Hobey’s unpredictable moves often tricked his own wings; they learned to lay back behind him and wait for rebounds. Because opponents were forced to double- or triple-team him, his Princeton linemates often found themselves shooting without a defender between themselves and the goalie.

After graduation, Hobey went to work for J. P. Morgan on Wall Street and continued his hockey career with the St. Nick’s. The club was mostly made up of Princeton, Yale and Harvard grads who competed in a league against regional semipro clubs that often imported ringers from Canada. These opponents played a rough brand of the game, and had no intention of being shown up by some blond-haired college boy. Hobey took everything they could dish out and returned the favor with one spectacular goal after another. Soon the sports pages were full of Hobey Baker headlines, and a new class of fans—many of whom attended games in evening clothes—began turning out in droves to watch him play. Crowds at St. Nick’s games swelled from several hundred to many thousands. Toward the end of his first year, St. Nick’s played five games against St. Michael’s, the top team in Canada. Hobey led his club to five stunning victories. Before they left, the Canadians offered him $3,500 to turn pro.

As the Great War raged on in Europe, Hobey began to dream of the ultimate competition—aerial dogfights. He had been in London in the summer of 1914 when the war began and nearly enlisted then and there. Early in 1917, he decided to join the U.S. Army and almost instantly became one of its top pilots. That summer, he shipped out to France. His training continued through the winter. He often held mock duels with Eddie Rickenbacker, whom he had known when they competed in wild, off-road “steeplechase” automobile races.

Hobey finally saw action in the spring of 1918. He found it so exciting that he could hardly sleep at night. He would go up three, four and five times a day—occasionally alone—looking for a fight. If his plane was being repaired, he would borrow another flyer’s, often returning it riddled with bullet holes. Hobey compared combat flying to what he loved about hockey and football: hurtling forward at great speed, darting and swerving on pure instinct, staying a step ahead of his opponents. By the end of the war, he had shot down three enemy aircraft. He also crashed behind enemy lines once but made it back safely.

In August of 1918, Hobey was asked to command a brand new squadron with two dozen planes painted Princeton orange and black. Excited at the opportunity, he grew increasingly frustrated as the aircraft failed to arrive. When they finally did, he had to whip his new pilots into shape. The war ended before he could do so and he was ordered to leave the squadron on December 21st.

That morning—a dreary, rainy morning—Hobey decided to take one last flight. His pilots tried unsuccessfully to dissuade him; “farewell flights” were considered by flyers to be bad luck. To compound matters, he decided to take another pilot’s plane—a Spad that had been problematic for weeks. After taking off and climbing sharply to 600 feet, the engine quit. Spads often crashed without serious injury to the pilot. Instead of wrecking the plane, however, Hobey aimed the nose down to regain flying speed so he could do a dead-stick landing. Before he could pull up, however, he ran out of air and crashed nose-first. He died in an ambulance a few minutes later, a few weeks short of his 27th birthday.

In the years that followed, the Legend of Hobey Baker continued to grow. The award for college hockey’s top player was named in his memory. Then, too, those who knew him quietly speculated that his crash had been the result of a suicide attempt. He would soon return to a world that offered no adrenaline-pumping challenges and he’d have to enter the business world—a world in which Hobey fully admitted he had neither the interest or acumen to achieve fame or fortune.