Sport: Football

Born: November 21, 1931

Died: November 19, 2007

Town: Phillipsburg, New Jersey

James Stephen Ringo was born November 21, 1931 in Orange, NJ and grew up in the town of Phillipsburg in the western part of the state. Phillipsburg is right across the Delaware River from Easton, Pennsylvania. The towns have a high-school football rivalry dating back to the early part of the century; their Thanksgiving Day game is one of football’s oldest traditions. Stateliner games against Easton often draw 20,000 fans or more.

The son of a factory worker, Jim was tough, focused, and loved to win. When he made the Phillipsburg varsity football team, he had visions of running for touchdowns with thousands of cheering fans calling his name. Jim told the coaching staff that he wanted to touch the ball as much as possible. They acquiesced, sort of. Jim became a center.

Jim was a solid student in high school. In fact, he was a class ahead of most boys his age. He had hoped to attend Muhlenberg College in Pennsylvania, where family friend Ben Schwartzwalder was coaching the football team. That plan changed during Jim’ s senior year, when Schwartzwalder was hired by Syracuse University. The Orangemen’ s once-mighty football program had fallen on hard times in the 1930s and 1940s. Syracuse needed a hard-nosed and committed coach to get it back on track. Schwartzwalder, a former paratrooper, was definitely the right man for the job.

With Schwartzwalder the new head honcho in Syracuse, Jim accepted a scholarship with the Orangemen in 1949. The 17-year-old stood 6’1″ and weighed less than 200 pounds when he arrived on campus. Despite his smallish size, Jim proved to be a capable two-way player. Schwartzwalder, a fitness fanatic, challenged the teenager to push himself and fulfill his potential as a player and a person. He made Jim a building block of a program that would reach national prominence by the youngster’s senior year—and compete for a national championship years later with players such as Jim Brown and Ernie Davis.

Everything came together for Syracuse in 1952, Jim’ s senior year. His quickness and power helped the Orangemen control the center of the line of scrimmage. The team went 7–2 in the regular season and climbed into the Top 20. Syracuse pulled off a rare quadruple, beating Boston College, Penn State, Colgate and Fordham. The Orangemen were invited to play Alabama in the Orange Bowl, but their magic eluded them against the Crimson Tide. In Jim’ s last game as a collegian, Syracuse was slaughtered, 61–6.

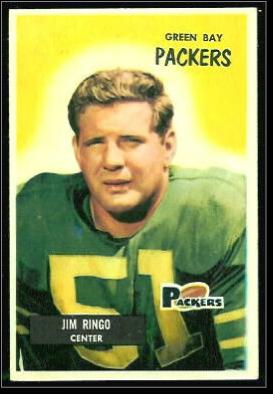

In the NFL Draft the following spring, Jim was selected in the seventh round by the then-lowly Green Bay Packers. He was not yet 21 when he reported to camp in Grand Rapids, Minnesota, and barely tipped the scales at 200 pounds. The Packers were used to undersized centers in the past, so they were not put off by Jim’s lanky frame. When Jim saw the other linemen in camp, however, he began to think he might be in the wrong business. Green Bay’s guards and tackles were all in the 230 to 250 range—and they were considered on the small side by NFL standards. After a few days of getting his butt kicked, Jim decided to save himself the trouble of being cut and went home to begin his life after football. The decision caught head coach Gene Ronzani by surprise. He dispatched a scout to find Jim and bring him back to camp.

Jim made the team and played five games as a rookie in 1953. He packed on another 20 pounds of muscle and made the starting lineup in 1954. In 1957, he was being recognized as one of the top offensive linemen in the game, and earned All-Pro honors for the first time. That year he battled mononeucleosis for much of the season. He was confined to a hospital bed Monday through Friday and was released to the team for the weekends!

Despite Jim’ s success, the Packers were a disaster on the field and in the box office. After the 1958 season, the NFL briefly considered folding the franchise. Things turned around with the hiring of Vince Lombardi in 1959. In camp that summer, Lombardi told his players that he had never been associated with a losing team, and he did not intend to start now. As the offensive coordinator of the Giants—and before that as one of Fordham’ s Seven Blocks of Granite—Lombardi had developed a feel for blocking schemes that he felt could create an unstoppable running attack. In Green Bay, he would build this attack around his one and only All-Pro offensive player, Jim Ringo.

Jim’ s skills were especially well suited to Lombardi’ s style. He was quick on his feet, good with his hands, and had tremendous balance, whether popping open a hole or spearheading Green Bay’ s pocket protection. What endeared him most to Lombardi was the fact that the coach could count the number of mistakes Jim made during a season on one hand.

The 1959 campaign marked the first of five consecutive seasons in which the unit of Jim (center), Bob Skoronski (left tackle) Forrest Gregg (right tackle), Fuzzy Thurston (left tackle) and Jerry Kramer (right tackle) lined up together as a starting five. Success was anything but instantaneous that first year. With four games left and a 3–5 record, Lombardi turned to young quarterback Bart Starr, whom he had benched earlier in the year. The future Hall of Famer led Green Bay to four stirring victories.

With a powerhouse offense and a tough defense, the Packers reached the NFL title game in 1960 but lost to the Eagles. The NFL expanded its schedule to 14 games in 1961, and the Packers swept to a second straight division crown, going 11–3 and leading the league in scoring with 391 points. The Green Bay running game was now working to perfection. As a result, Starr was able to open up the team’s aerial attack. He set a club record with 2,418 passing yards. Jim Taylor, meanwhile, racked up over 1,300 yards on the ground. Paul Hornung, playing Sundays on a weekend pass from the military, was less effective as a runner than in past seasons, but he handled the team’ s kicking duties with his usual aplomb. A third back, Tommy Moore, picked up the slack in an expanded role from the previous season.

There were several seasons during the early 1960s when Hornung was either less than 100 percent or altogether unavailable. The fact that the Green Bay attack barely missed a beat was a tribute to the much-heralded offensive line. Although centers typically don’t get a lot of ink—less even than more-visible guards and tackles—Jim’ s work was recognized in the press. Green Bay fans were certainly aware of his specialties. Few were better at picking off the middle linebacker on plays up the gut or burying the defensive tackle on sweeps. Both skills required tremendous quickness from a center.

The Packers were a supremely confident bunch by this time. Their pregame routine said it all. Lombardi would disappear from the locker room about 10 minutes before kickoff, leaving the players to do some last-minute bonding and gut-checking. At the appropriate time, Jim would summon Lombardi back in and the coach would deliver a short speech telling his men how proud he was to be their leader. From that moment on, the team was ready to go to work.

The Packers had honed their smashing attack to a fine edge by the 1961 NFL Championship game. Lombardi’s old club, the Giants, had survived a three-way tussle in the East to earn a place on the field on New Year’s Eve in Green Bay. New York made a show of it for exactly one scoreless quarter, after which the Packers scored three touchdowns and a field goal. They took a 24–0 lead into the locker room at the half. Everyone knew what was coming next. For two miserable quarters, the Giants had to absorb Green Bay’ s punishing ground game. Hornung, Taylor and Moore smashed into the New York defense again and again. The final score on this sub-freezing day was 37–0.

It hardly seemed possible, but the Packers were even better in 1962. The offense was literally uncontainable. Taylor took the rushing crown from Jim Brown’ s head and Starr was the NFL’ s most efficient passer. Four of the five offensive linemen were honored as All-Pros, including Jim, who contracted a nasty staff infection during the year. For six weeks, he spent Monday through Friday in a hospital bed and then suited up for games on the weekend, just as he had in 1957.

The 1962 title game paired the Packers with the Giants again, this time in Yankee Stadium. On a frigid, windy Wisconsin-like afternoon, passing was not an option. Jim and his linemates earned their pay, jousting with Rosey Grier, Andy Robustelli, Sam Huff, Jim Katcavage and Dick Modzelewski in a line-of-scrimmage street brawl. The Packers led 10–0 at the half.

New York grabbed the momentum in the third quarter after blocking a Green Bay punt. With the score 10–7, the Packers regained control and added a final field goal to win their second straight championship, 13–7. Jim spent much of the day looking for Huff, who spent most of the day looking for Taylor, who carried the ball 31 times for 85 hellish yards.

The law of gravity seized the Packers in 1963. Hornung was suspended for gambling, and Starr was injured for a month. The surprising Bears, who beat Green Bay at Lambeau Field on opening day, proved they were for real with a 26–7 victory in their November rematch at Wrigley. Chicago finished 11–1–2, while the Packers went 11–2–1.

The post mortem on this disappointing season included a change of address for Jim. Lombardi traded him to the Eagles. The story goes that, after yet another All-Pro campaign, Jim wanted a raise from the team and brought an agent into Lombardi’ s office to negotiate it for him. The coach excused himself from the room, and when he returned he informed Jim’ s agent that he was in the wrong city to discuss his client’ s contract. Jim had been dealt to Philadelphia!

Jim welcomed the chance to play closer to home. He enjoyed another Pro Bowl campaign in 1964. Though he was still one of the NFL’s best, he began yielding ground to young Mick Tinglehoff of the Minnesota Vikings as the top center in the game. In 1965, Jim received yet another Pro Bowl invitation and garnered a few All-Pro votes. After 13 seasons, however, he was beginning to show the wear and tear of all the trench warfare. That did not mean Jim was sitting out games or missing starts. Quite to the contrary, he was putting the finishing touches on what would end up as an NFL-record 182-game playing streak. The final 56 games came in an Eagles uniform. The 1967 season would be Jim’ s last as a player.

Jim continued to be employed in the NFL as a line coach and offensive coordinator. His work with the Buffalo Bills linemen in the 1970s helped OJ Simpson blossom into a record-breaking rusher. He also helped build the great Buffalo teams of the late 1980s and early 1990s, but was not around to share in their triumphs. In 1988, a play spilled over the sidelines and Jim’s leg was badly broken and he had to retire. In 1996, Jim was diagnosed with Alzheimer’ s Disease. He died in 2007.

Jim Ringo played in 10 Pro Bowls, and was a six-time first-team All-Pro. He was enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1981.