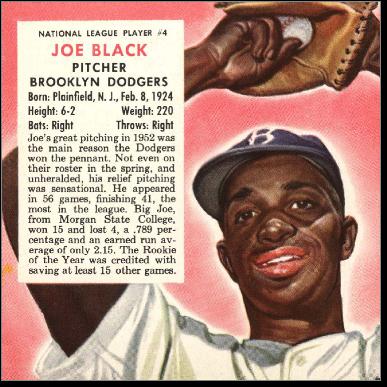

Sport: Baseball

Born: February 8, 1924

Died: May 17, 2002

Town: Plainfield, New Jersey

Joseph Black was born on February 8, 1924 in Plainfield, NJ. His family owned an auto repair shop in the poor section of town and lived in a modest house next door to the business. Joe attended Plainfield High School, which had strong sports teams. Joe was friends with Donald Van Blake, who was a class ahead of him. Van Blake was an African-American tennis pioneer whose exhortation Tennis! Tennis! Tennis! encouraged thousands of young people in the region to get on the courts. Joe’s sport was baseball, although he also competed for the football and track teams.

Joe received a scholarship to Morgan State College. He pitched for the Bears’ baseball team, ran hurdles and threw the javelin for the track team, and was an all-conference end for the football team. He was also a member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity, which counts among its ranks Count Basie, Bill Cosby and Langston Hughes.

During the summers, Joe played for the Baltimore Elite Giants, whose home base was near his college campus. He pitched for Baltimore from 1943 to 1950, playing in three Negro League All-Star Games. He got his first contract after he and Cal Irvin (Monte Irvin’s brother) were caught badmouthing the Giants from the stands. Sitting behind them was Vernon Green, an executive with the club. He said If you think you’re so good then why don’t you try out. Joe did…and made the team at the age of 19. He went into the army shortly thereafter.

The Brooklyn Dodgers signed Joe in 1951 and, after one year in the minors, he became their closer as a 27-year-old rookie. He led the league with 41 games finished and fashioned a 15-4 record with 15 saves and a 2.15 ERA, while pitching all but two of his 56 games in relief. Joe earned Rookie of the Year honors and actually came within a handful of votes of beating out Hank Sauer and Robin Roberts for the MVP.

The Dodgers dominated the National League that year, finishing four games ahead of the defending champion Giants. Manager Charlie Dressen turned his ace reliever into a workhorse starter against the Yankees in the World Series. The move looked like a stroke of genius after Joe defeated New York in Game One. It marked the first time an African-American pitcher earned a W in postseason play. Dressen sent him to the mound twice more in the series. Joe was on the wrong end of a 2–0 shutout in Game Four. In Game Seven, he pitched into the sixth inning, leaving behind 3–2. The Yankees tacked on a fourth run and held Brooklyn scoreless the rest of the way. Despite taking two losses, Joe’s ERA in the series was 2.53, tops among the Dodger starters.

The workload of 1952 took a lot out of Joe. He wasn’t nearly as effective the following season. When the team encouraged him to add new pitches to his repertoire, he lost the consistency on his fastball and curve—his bread-and-butter pitches. His ERA soared over 5.00 and, in the 1953 World Series, he pitched just one inning and gave up a long home run to Gil McDougald.

Disenchanted with their falling star, the Dodgers sent Joe to the minors for most of 1954. He pitched well for Montreal, earning another chance with Brooklyn in 1955. He made the club but wasn’t around to participate in their World Series championship. That June, the Dodgers sent him to the Reds for a player to be named later.

Joe pitched well for the Reds in 1955 and 1956, but he was only a shadow of the player who took the league by storm in 1952. In 1957, Joe opened the year with Cincinnati’s top farm club, in Seattle. He was purchased by the Phillies, who sent him to Tulsa and never called him up. They released him in July and he caught on with the Washington Senators that August. He got shelled in seven appearances. When no teams called that winter, Joe decided it was time to move on to his next career.

Finding work was not a problem. Joe was known as “Gentleman Joe”—everyone who met him liked him. He work for a time as an advisor to Major League Baseball and, along with Jackie Robinson, lobbied for pension for their fellow Negro Leaguers. Later, Joe became an executive with Greyhound in Phoenix, Arizona. He also wrote a syndicated column for Ebony Magazine. Joe even did a little acting, appearing in an episode of The Cosby Show alongside his frat brother.

Joe ran the BAT program in Phoenix and also did some community relations work for the Diamondbacks after they came to town. He died of cancer at the age of 78 in 2002. Baseball honored Joe by naming the MVP Award of the Arizona Fall League after him.