Sport: Baseball

Born: May 9, 1854

Died: October 14, 1929

Town: Jacobstown, New Jersey

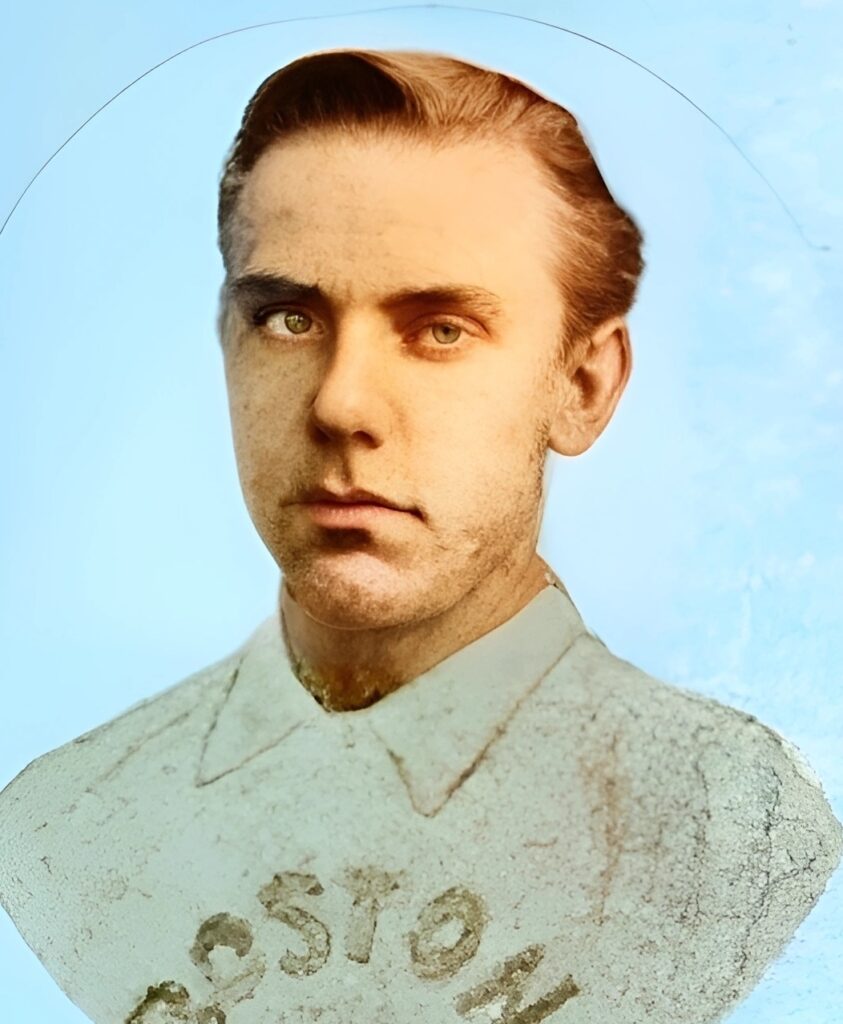

Joseph Emley Borden was born May 9, 1854 in Jacobstown, NJ to Sarah Ann and John Borden, a successful merchant in Burlington County. Joe began playing baseball as a teenager after his family moved to Philadelphia. He was short and skinny, but a good athlete with a strong arm that served him well in the pitching box. Hurlers at this time threw underhand and Joe’s swift delivery made him the ace for an amateur team called the JB Doerr Club.

In 1875, the Philadelphia White Stockings—members of the National Association—found themselves short on pitching with a game against their city rivals the Athletics coming up. Joe had just pitched a good game against the A’s, so the White Sox offered to pay him to pitch until they found a more experienced replacement. Joe lost that game and the next one, to Chicago. Two days later, however, Joe made history in a return match with Chicago. He pitched the first no-hitter in the history of professional baseball. A week later, Joe shut out the St. Louis Brown Stockings.

When Joe’s replacement arrived, he was given the heave-ho and went back to amateur ball. The Boston Red Caps—the dominant team in the Association— jumped on the opportunity and offered to sign Joe. Because he planned to go into the family business—and because his family didn’t approve of ball-playing—he demanded a three-year contract and got one, very likely the first in history. Joe pitched professionally under the name Josephs.

When the 1876 season began, Joe was on the mound for Boston in the inaugural game of the newly christened National League. He beat the Philadelphia Athletics on the road for the first win in NL history. The Red Caps were managed by Harry Wright and featured some of the game’s best hitters, including Newark’s Andy Leonard and Hall of Famer Jim O’Rourke.

In Boston’s first home game, Joe unleashed a wild pitch that hit a woman in the face. The game was halted while Joe apologized and later he called on her at home to see how she was doing. In another game that spring, Joe was the victim of a hidden ball trick, perpetrated by first baseman (and fellow New Jerseyan) Everett Mills of Hartford. Joe may have made history yet again in May when he beat Cincinnati, 8–0. The box score in the paper listed two hits against him, but later research showed those were probably walks. That would have been the first no-hitter in NL history.

Unfortunately, the rest of the year did not go Joe’s way. His pitching was wild and opponents often hit him hard. He pitched his last big-league game on July 15th and was released in August. His record was 11–12.

There was just one problem: Joe’s contract, which had been drawn up by a lawyer, was rock-solid and he was owed two more years’ salary. The team tried to make him quit by asking him to do groundskeeping duties, but he knew what they were up to and simply complied. Boston’s president, Arthur Soden, finally bought him out prior to the 1877 season. This experience contributed to Soden’s distaste for anything resembling players’ rights and, three years later, he would unveil the instrument known as the Reserve Clause.

Joe went into the footwear business in Philadelphia and later became an officer at a bank, joining the ranks of Main Line society. He passed away at the age of 75.