Sport: Basketball

Born: September 22, 1971

Town: Jersey City, New Jersey

Luther A. Wright Jr. was born September 22, 1971 in Jersey City, NJ. He was the eldest of three children born to May and Luther Sr.. Height ran in the Wright family. May was a shade under six feet, Luther Sr. was 6’3” and Luther’s grandfather was seven feet tall. Luther endured a tortured childhood. In a book he later authored, he detailed how he was abused by three relatives, beaten up by older kids in the neighborhood, and made fun of because of his immense size—called names like “Lurch” and “Bigfoot.” At home, he went by “Junior.” There, his size was unremarkable; it was the only place he felt safe.

By fifth grade, Luther was taller than his teachers. In high school, he grew to 7’2” and wore a size 21 sneaker. Then, one day, his mother announced that she and her husband were splitting up. She moved Luther and his brother from their home into the projects with Luther’s grandmother, and things only got worse.

Luther’s salvation, it was thought, would come on the basketball court, where he demonstrated agility and coordination no matter how tall or how wide he got. The only problem was, Luther didn’t really like basketball.

Even so, he became a high-school sensation—first at St. Anthony’s in Jersey City for Bob Hurley and then at Elizabeth High, which he led to a state title as a senior. In 1990, Luther was named a McDonald’s All-American. Though highly recruited, he decided to stay close to home and accepted a scholarship from P.J. Carlesimo at Seton Hall. Luther skipped his first season because he was academically ineligible, but improved his test scores and ended up playing two inconsistent varsity seasons beginning in 1991–92. In 1992–93, Luther averaged 9.0 points and 7.5 rebounds a game.

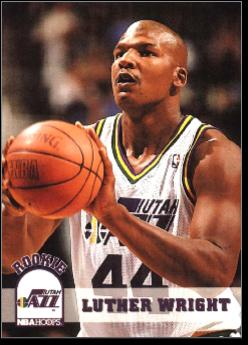

The Utah Jazz selected Luther in the first round of the 1993 NBA Draft. The thought of Karl Malone and John Stockton working with a 7’2” center had Jazz fans penciling in multiple championships. Luther’s agent negotiated an unusual $5 million contract, which guaranteed the Jazz would pay him $153,000 a year for 25 years.

Luther had driven Carlesimo mad with his lack of focus and intensity. Now Utah coach Jerry Sloan had to deal with him. Luther loafed through practices and early-season games. He also smuggled a puppy on board a team flight, triggering much head-shaking. But that was nothing compared to an episode in January of 1994, when he went on a psychotic bender for several hours, brandishing a weapon, smashing car windows and hammering on a dumpster at a Utah rest stop.

For a gentle giant, it was totally out of character. Luther was taken into custody and brought in for psychiatric treatment. He eventually was diagnosed with bipolar disorder. His new medication did not help and, at one point in 1994, he tried to take his own life. Luther had logged just 92 minutes as an NBA player at that point. He would never appear in another NBA game.

In his late 20s, Luther tried to work his way back into shape, but never made it back to the NBA. His downward spiral continued for years, and he eventually ended up as a crack addict, homeless in Newark, sometimes walking barefoot in the street in the dead of winter. It got so bad that he had to have a couple of toes amputated. At one point he weighed over 500 pounds.

In 2005, Luther began turning his life around, entering a drug counseling program, becoming active in the church, joining a gospel group, DJ-ing at Seton Hall games and finding a wife. He also returned to Seton Hall to fulfill a promise to his mother that he would earn a degree. Having become something of an urban legend, Luther decided to write a book in 2010 to set the record straight. It was entitled A Perfect Fit.

Unfortunately, Luther lapsed back into homelessness after his marriage ended and his son was killed. He would be spotted in and around Newark from time to time, acting erratically and occasionally shoeless, and eventually lost all of his toes. Finally, in 2021, Luther left New Jersey and moved in with his sister, a nurse’s assistant, in Augusta, Georgia. His money from the long-term Jazz contract—much of it squandered on drugs—ended that year.