Sport: Track and Field & Football

Born: December 9, 1933

Town: Plainfield, New Jersey

Milton Gray Campbell was born December 9, 1933, in Plainfield, NJ. His father was a cab driver, his mother a maid and his older brother, Tom, the star of the racially mixed Plainfield High track team. Milt competed for the swim team (he was an All-American swimmer) and football team at PHS, as well as the track team. He was freakishly large and freakishly powerful as a teenager.

Once, during a wrestling meet, Milt agreed to stand in for a sick wrestler. He pinned the boy who went on to win the state heavyweight championship that season in under two minutes. Milt’ s track coach, Harold Bruguiere, said he was the greatest all-around athlete he’d ever seen. Milt set state records in the hurdles and high jump, and was the’ star running back for the Cardinals football varsity.

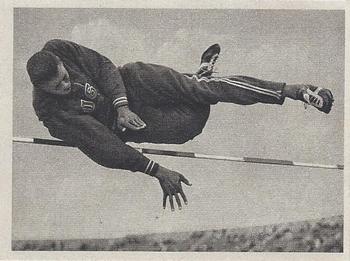

Following his junior year, Milt traveled to Helsinki, Finland as a member of the U.S. track & field team (left). He competed in the decathlon against defending gold medalist and teammate Bob Mathias. Mathias won by the largest margin in history, but the 18-year- old Campbell finished second, ahead of well-known international stars such as Vladimir Volkov, Josef Hipp and teammate Floyd Simmons, who took the bronze for the second time in 1952. Milt dominated in the hurdles and sprints, but struggled in the pole vault and 1500 meters. Even so, a high-schooler with a silver medal made for great international headlines.

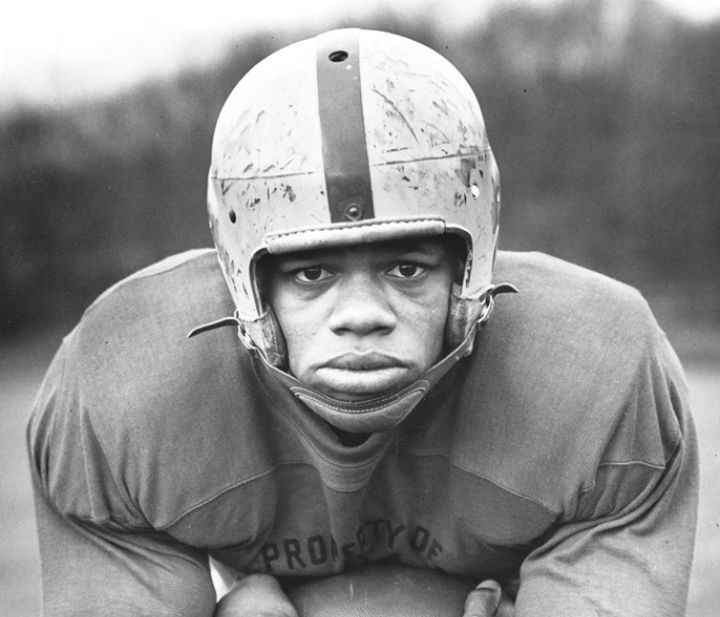

Back in the New Jersey, Milt played his senior season for the Plainfield High football team. He stood 6’3″ and weighed 210 pounds, with powerful legs and blazing speed. He was described by The New York Times as the second coming of Bronko Nagurski. That spring, Milt won the AAU decathlon competition.

Milt accepted a football scholarship from Indiana University, knowing he would also concentrate on track. He was the AAU and NCAA high hurdles champ in 1955. He also won a varsity letter for the Hoosiers football team. A gifted two-way player, he had three interceptions in a game against Ohio University and caught a game-winning bomb sprinting out of the backfield against Michigan.

In 1956, Milt returned to the Olympics, once again competing in the decathlon. He had planned to go as a hurdler, but finished a surprising fourth in the Olympic trials, leaving him off the team. The decathlon was almost an afterthought—the experts were picking UCLA’ s Rafer Johnson to blow away the field, having just set a world record for points in the event.

Alas, Johnson would have to wait until 1960 for his gold medal, as Milt won his first event, the 100 meters with a time of 10.8 seconds, and never looked back. He finished no worse that second in 7 of the 10 events—including wins in the shot put and 100 meters hurdles—and easily won the gold medal. Milt could have broken Johnson’ s US record, but came up 20 inches short of his personal best in the pole vault. He did set a new Olympic record, however.

Perhaps the most amazing thing about Milt’ s triumph was that, in his entire career, he competed in only five decathlons—the two Olympics, the two Olympic trials, and the 1953 AAU decathlon. He is also the only Olympic decathlon gold medalist to hold a world record in another event; in 1957, Milt set both the indoor and outdoor world records in the 60-yard hurdles. He twice beat Olympic gold medalist Lee Calhoun in Calhoun’s signature event. Milt’ s final race was on a muddy track in Southern California. He finished the 120-yard hurdles in 13.4 second.

In the late-1950s, Milt turned his attention to pro football. He was drafted by the Cleveland Browns, a team that had won championships by embracing African-American players. He roomed with Jim Brown in 1957. Milt found a cooler-than-expected reception from the Cleveland brass, and suspected the reason was that his wife, Barbara, was white. The Giants expressed some interest in obtaining Milt, but nothing ever materialized. He later played with Montreal and Hamilton of the Canadian Football League, but Milt felt just as much discrimination in the CFL.

After retiring from sports, Milt lived in Canada until 1967. Spurred on by the Newark riots, he returned to the U.S. to start an alternative school in that city. He made a good living as a motivational speaker, often lecturing on the importance of education. He has also run programs for underprivileged children. His son, Grant, became a world karate champion. Milt was inducted into the National Swimming Hall of Fame and Track & Field Hall of Fame—the only athlete to be enshrined in both.