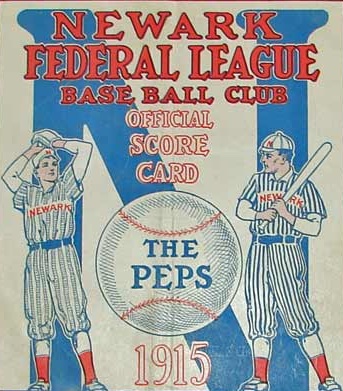

The last big-league baseball team to call New Jersey its official home was the Newark Peppers, in 1915. They played one season, in the Federal League, a rival circuit to the National and American Leagues that operated as a major league in 1914 and 1915. The “Peps” began life as the Indianapolis Hoosiers. Their principal owner was banker Harry Sinclair. Sinclair was one of the moving forces behind the Federal League, which began as an independent minor league in 1913 and then lured several stars away from the NL and AL when it declared itself a major-league equal a year later. The Hoosiers poached Cy Falkenberg, Frank LaPorte and Bill McKechnie from their respective clubs.

The Hoosiers rewarded Sinclair with the 1914 Federal League pennant, edging the Chicago Feds by a single victory. The ball club’s star attraction was Benny Kauff, a former New York Highlanders farmhand. He was the offensive standout of the league in 1914, leading all hitters in runs, stolen bases and batting average. LaPorte, hitting cleanup behind him, was the RBI king with 107.

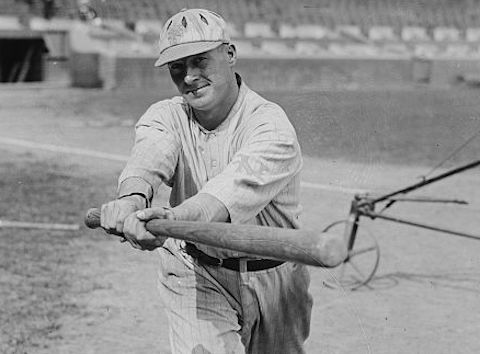

The success of the Hoosiers prompted Sinclair to relocate the team to New Jersey for the 1915 season. The Federal League believed it could compete with the Yankees and Giants in New York and, despite the fact it was blocked from actually placing a team in Manhattan, felt that Newark (the team’s stadium was actually in adjacent Harrison) would be a good stepping stone. The Brooklyn Tip-Tops (also a Federal League club) were none too happy about another FL team moving into an already-crowded market. They were placated by the transfer of Kauff (left) to their club.

Without their slugging star, the renamed Peppers struggled to score. They no longer had a hitter who could carry the club, depending instead on solid-but-unspectacular seasons from McKechnie (who became the Peps’ player-manager) and outfielders Al Scheer, Vin Cambell and Edd Roush. Roush, the youngest starter at age 22, led the club with 164 hits. No one knew it then, but he was embarking on what would be a Hall of Fame career. McKechnie would also reach Cooperstown, though as a manager. He was the first to pilot three different teams to National League pennants.

The team’s pitching was bolstered by the acquisition of Ed Reulbach, a superstar with the Cubs in his 20s. Now 32, he had just enough gas in the tank to befuddle Federal League batters. Earl Mosely, a 19-game winner the year before for the Hoosiers, had a terrific year in 1915, leading the league with a 1.91 ERA. He pitched in hard luck, however, finishing 15–15.

The only native New Jerseyan on the Peppers was Rupert Mills, who was born in Newark. Mills was a Notre Dame grad who played football with Knute Rockne and also starred for the baseball and basketball teams. He shared first base duties with Hap Huhn, a rookie who had originally signed with the team thinking they would play near his hometown, Indianapolis.

The Peppers actually started the season strong, hanging onto first place into early May. But 11 losses during the month sent them tumbling into fourth place. The team rallied in August to recapture the top spot thanks to Reulbach, who was on his way to a 21-win season. However, the Peppers faded down the stretch and ended up fifth in a razor-thin five-team pennant race. The Chicago Feds (aka Whales) finished atop the standings, just six games in front of the fifth-place Peps. The St. Louis Terriers were second in history’s tightest-ever finish.

Prior to the 1915 campaign, the owners of the Federal League clubs filed an antitrust lawsuit against the National and American Leagues. The case ended up in front of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who encouraged the two sides to find an amicable middle ground rather than issuing a ruling that would have been instantly appealed. The owners in the more established leagues dragged out negotiations through the 1915 season and, seeing Federal League attendance wane, made their move and bought out four of the Feds—including Sinclair’s New Jersey team—and the league soon folded. As part of the peace settlement, two Federal League owners were allowed to buy the struggling Chicago Cubs and St. Louis Browns and merge their respective rosters.

WHERE DID THEY GO?

After the Federal League folded its tent in December 1915, the Newark Peppers were dispersed throughout baseball in a flurry of deals:

McKechnie, Roush and catcher Bill Rariden (left) were sold to the Giants. A year later, McKechnie and Roush were traded—along with Christy Mathewson—to the Reds. It was the only time three future Hall of Famers were sent as a package to another team in a trade.

Moseley and Huhn also ended up on the Reds. Huhn was behind the plate when Fred Toney and Hippo Vaughn pitched their epic double no-hitters. Neither played in the big leagues past 1917.

Reulbach won just 7 more games before calling it a career. Some historians consider him the best pitcher of his era who is not in the Hall of Fame.

Campbell, Scheer, LaPorte, and shortstop Jimmy Esmond never saw action in the majors again.

It’s worth noting that many a baseball career ended after 1917, when hundreds of major leaguers joined the military after America entered World War I. Among those who saw action in Europe was “Rupe” Mills (right), the Peps’ part-time first baseman. He captained an artillery unit in France. Mills was the only player whose contract the Peppers not able to unload. Having graduated from Notre Dame with a law degree, he signed with Newark on the condition that he could alter the standard contract to guarantee him a $3,000 salary for 1915 and 1916—a very unusual deal for an unproven player. Newark’s calculation was that they would recoup the money because Mills was a local celebrity.

Although the Federal League ceased operation, the Peppers remained a business entity and therefore, Mills claimed, they had to pay him for his 1916 season. The $3,000 was at least three times what he would have earned as a minor leaguer. The Peppers’ general manager pointed out that they would do so only if he showed up—in shape and in uniform—at Harrison Field every day ready to play. Mills called his bluff and did just that for the first two months of the season. He would pitch off the mound, run the bases, toss up balls and hit them and give occasional interviews to sportswriters. Finally, the exasperated Peppers paid Mills off and sold him to a minor league team, losing a couple of thousand dollars in the deal.

Who enjoyed the best year in 1916? Probably Harry Sinclair.

He not only turned a hefty $2 million profit on the Peps, but also formed Sinclair Oil in 1916. During the 1920s, Sinclair also owned Rancocas Stable in South Jersey, which had been one of the nation’s best in the late-1800s. Sinclair sunk millions into the operation and saw his horses win three Belmonts and one Kentucky Derby. He also owned the castle-like mansion on Fifth Avenue and 79th Street (left), which still stands.

Alas, the 1920s also saw Sinclair indicted and convicted of fraud and corruption in the Teapot Dome scandal. He actually served prison time. He continued running Sinclair Oil after his release, retiring in 1949.