Sports: Football & Basketball

Born: April 9, 1898

Died: January 23, 1976

Town: Princeton, New Jersey

Paul Leroy Robeson was born April 9, 1898 in Princeton, NJ. His father, William, was a former slave who escaped during the Civil War. He became a minister known for his outspoken views on social injustice. His mother, Maria, was from a prominent abolitionist family. She died in a house fire when Paul was six years old. Paul’s father moved the five Robeson children to Westfield and later to Somerville. At Somerville High School, Paul excelled in academics, acting, singing and sports. He received a full scholarship to Rutgers in 1915.

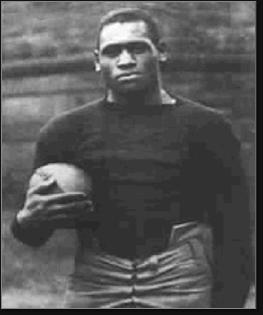

Paul was the only African-American student on the Rutgers campus. He was a brilliant student and one of the school’s greatest all-around athletes. He earned letters in baseball, basketball, track & field, and football. Paul played end, which at the time was primarily a blocking position on offense and a tackling position on defense. He learned from one of the best, Bob Nash, who would go on to become a famous pro. Paul was good enough at both to be named an All-American as a junior and senior. This despite the fact that coach George Sanford had to bench Paul against Southern schools, whose players refused to share the field with a person of color.

Walter Camp, the ultimate authority on football during this era, called Paul the greatest defensive end that ever lived. Lou Little, coach of Columbia, gave Paul even higher praise, saying there had never been a greater player, period. Although Paul faced racism on campus and, from time to time, on his own practice field, he was elected class valedictorian. In his graduation address, he predicted that he would be New Jersey’s first black governor.

Paul did a bit better than that. He attended Columbia Law School, paying his way as both an entertainer and athlete. His booming bass singing voice riveted audiences. On the weekends, Paul suited up for the Akron Pros and Milwaukee Badgers of the American Professional Football Association, the forerunner of the National Football League. He also coached football, serving as an assistant at Lincoln University.

Paul even played pro basketball, competing for the St. Christopher Club, whose nickname was the Red & Black Machine. Many of the players he faced on the hardwood were stars of early Negro League baseball, including Oscar Charleston and Cum Posey. Paul played the pivot, teaming with ball-handing whiz Fats Jenkins to win a couple of Colored World Basketball Championships. Jenkins later was a star on the Harlem Rens, and was enshrined in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

Paul turned his attention to the law after graduation. He was the only African-American attorney at the highly regarded Manhattan firm of Stotesbury & Miner. He quit after a white secretary refused to take dictation from him.

Paul gave up pro sports but continued to act. In 1924, he bowled over audiences in Eugene O’Neill’s The Emperor Jones, launching his stage career. In 1928, Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein wrote the song “Ol’ Man River” in the musical Showboat with Paul in mind. He played the part of Joe and performed what is still considered the definitive version of this song. From there, he took the title role in Shakespeare’s Othello. He also appeared in several films in the 1930s.

Never shy about speaking out on race relations and other social issues, Paul became drawn into international politics during the Spanish Civil War. He reached the height of his fame as both a performer and activist, and gained universal respect for his work in both arenas. In 1943, Paul demanded an audience with Major League Baseball owners during their winter meetings and got it. He delivered an impassioned lecture on the injustice and stupidity of the color barrier.

In the late-1940s, Paul was branded as pro-Communist for his views and became an object of intense interest for the FBI in America and the CIA abroad. In 1950, the State Department cancelled his passport. When he refused to sign an affidavit stating he was not a Communist, he found himself blacklisted. In some football histories, the All-America teams from 1917 and 1918 only listed 10 positions—the name Paul Robeson was completely omitted.

Paul’s health began to fail in the 1960s. His mental state deteriorated, too, in no small part because of being under constant surveillance. After living in England for many years, he returned to the US, living in New York and Philadelphia. In his final years, Paul was showered with awards and honors. In 1973, he celebrated his 75th birthday at Carnegie Hall before an audience of 3,000 admirers. He passed away in 1976 after suffering a stroke.

In the 1990s, Paul’s college football records were restored. In 1995, he was posthumously enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame.