Sport: Basketball

Born: June 23, 1930

Died: March 14, 2001

Town: South Orange, New Jersey

Walter F. Dukes was born June 23, 1930 in Rochester, NY. He moved to New Jersey as a teenager to attend Seton Hall Prep in West Orange. An unusually agile big man with great stamina and energy, Walter played basketball and run track for East High School in his hometown, and was successfully recruited by Seton Hall University after Bob Davies tipped off coach Honey Russell about him. Walter spent one year at Prep acclimating himself to his new surroundings, but schoolwork was never a problem with him—he was one of the brightest kids in his class.

NCAA rules dictated that freshmen could not participate in varsity basketball, so Walter spent a year on the frosh squad, which went 39–1. Many fans came early to watch the freshman game and then left before the upper classmen took the court.

Walter had long arms, sharp elbows and eerily good timing as a rebounder. He was also an intimidating defender. On offense, most of his buckets came within a few feet of the rim, but he was good for 20 points and/or 20 rebounds most nights for the Pirates. Walter and Richie Regan were the stars of the 1951–52 squad, which reached the finals of the National Invitation Tournament in Madison Square Garden. The 1952–53 team went 31–2 and won the NIT, with Walter copping MVP honors. Walter hauled down a record 734 rebounds that season and was a first-team All-American, averaging over 26 points and 20 rebounds per contest.

Walter was taken in the NBA Draft as a territorial pick by the Knicks that spring, but instead signed with the Harlem Globetrotters in 1953. Owner Abe Saperstein made a big show of the signing, rolling a wheelbarrow full of silver dollars into Toots Shor’s as a bonus on top of the reported $25,000 Walter would earn. That was more than twice what first-round picks made in the NBA at the time. He spent two years touring with the Trotters before joining the Knicks for the 1955–56 campaign. Walter claimed the distinction of being the league’s first true seven-footer.

Walter was slowed by a knee injury as an NBA rookie and was frequently in conflict with coach Vince Boryla. He also demonstrated a propensity for drawing fouls in bunches. In practice, he occasionally injured teammates with his rough play. Just prior to the 1956–57 opener, the Knicks traded him to the Lakers for three players, including Slater Martin. Walter would be asked to help plug the hole created by the retirement of George Mikan.

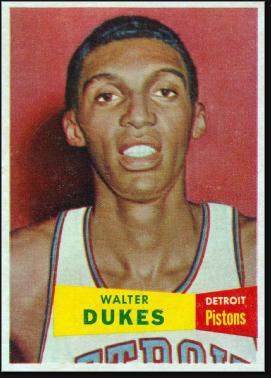

The Lakers’ front line that season might have been the toughest rebounding threesome in NBA history. Walter, Vern Mikkelsen and Clyde Lovelette combined for an average of 33.5 boards a game. The team reached the West finals but were swept by Bob Pettit and the Hawks. That summer, Walter was traded to the Detroit Pistons for center Larry Foust. Walter enjoyed the finest years of his career in Detroit. He was an All-Star in 1960 and 1961, and pulled down more than 1,000 rebounds during the 1960–61 season. He had 15 rebounds during the 1960 All-Star Game to lead all players. Those who played against Walter in college said he was never as good in the NBA. They suspected the seasons he lost playing with the Globetrotters prevented him from evolving into a truly great pro.

Walter’s foul troubles continued. He led the NBA in this category during his first two seasons in Detroit, and averaged close to 5 a game throughout his career. He would end up with more career disqualifications than anyone other than his old teammate, Mikkelsen. Walter fouled out 121 times—roughly once every five games. That being said, he was an equal-opportunity hacker; at one time, his teammates asked him to wear a cowbell so they could hear him coming in practice.

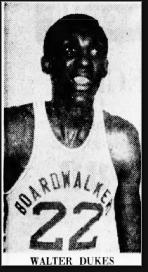

Walter was prepared for life after the NBA. He had taken law courses during the off-season and received his degree from New York Law School in 1960. He was admitted to the Michigan bar and practiced in that state while playing for the Pistons. The club cut Walter after the 1962–63 season, so he joined the Eastern League, which played games on weekends. He returned to New Jersey and played for the Camden Bullets, Trenton Colonials and Asbury Park Boardwalkers before finishing his playing days in 1969 with the Scranton Miners.

Walter had been making investments in real estate during the 1960s and was also an admired civil rights attorney. Sadly, a 1971 auto accident left him with a traumatic brain injury, and his world soon imploded. He was suspended from the Michigan Bar in the early 1970s for failure to pay his dues, but he continued to do legal work in the Bronx without a license. He was found guilty of practicing law without a license in New York in 1975.

Walter later moved back to Detroit. He married and had a daughter, yet he slowly withdrew from the world over the next quarter-century. He refused invitations from the Pistons to appear at events, and Seton Hall at one point asked the FBI to locate Walter, not knowing if he was alive or dead. Early in 2001, after friends and family hadn’t heard from Walter in several weeks, they checked his apartment and found him dead at the age of 70.