WILL THE REAL BOB MAXWELL PLEASE STAND UP?

Everyone during the Depression had a side hustle. If someone tells you otherwise, they’re not telling the truth. College basketball players during this time of financial struggle could (and often did) earn a few extra bucks suiting up for barnstorming or even professional league teams—performing under assumed names, of course, so as not to jeopardize their NCAA eligibility. While their real names might have been familiar to fans, their faces rarely were; TV was still years away and newspapers rarely if ever sent photographers to cover pro or college games.

That being said, fans in upstate New York had to have had a glint of recognition when Bob Maxwell took the floor for the Syracuse Reds during the winter of 1939–40. He stood a muscular 6’5” and demonstrated quickness and skill that was highly unusual for a big man. His hook shot was money in the bank and hard to defend because of his wide body. He was also a dominant rebounder. The Reds played in the rough-and-tumble New York State League and they needed a center like this in the worst way. Bob Maxwell, whom the Reds reported came from “the courts of New York City,” proved to be an excellent fit.

Just one problem…Bob Maxwell was a 24-year-old senior on Seton Hall’s varsity basketball team.

His real name was Ed Sadowski, and he was the high-scoring All-Eastern center for the Pirates’ , who were on their way to the school’s one and only undefeated season. Oh, and he was also the team’s captain. Coach Honey Russell no doubt suspected something was amiss, but Russell himself had worn multiple uniforms in the same season during the 1920s and early 1930s, so he probably looked the other way.

Alas, Bob Maxwell’s pro career came to an abrupt end when he injured his knee in a college game in February.

Ed Sadowski’s pro career began in earnest the following fall, when he signed to play with the Detroit Eagles of the National Basketball League. He was the leading scorer on a club that included veteran Rusty Saunders and young guns Bob Calihan and Buddy Jeannette.

As for the Reds, they found a replacement for Maxwell/Sadowski in Mark Haller of Syracuse University, who signed with them after he had completed his senior season for the Orangemen and could play under his own name. The Reds would go on to compete in the World Pro Tournament in Chicago that spring and Haller was the top scorer in their three games.

Sadowski served in the Army Air Corps during World War II, but because he was in constant demand, he continued to play here and there for pro teams when he could arrange a leave or furlough. He was a member of Barney Sedran’s Wilmington Blue Bombers, who won the American Basketball League title in 1942. After the war, Sadowski lost some of his agility, but he was still a big name in the pros. When the Basketball Association of American (forerunner of the NBA) began play, Sadowski signed with the Toronto Huskies. He scored what is regarded as the NBA/BAA’s first basket on opening night, against the Knicks.

In 1947–48, Sadowski was reunited with Honey Russell as a member of the Boston Celtics. His teammates included New Jersey stars Connie Simmons, Mike Bloom and another Seton Hall alum, Chuck Connors. Sadowski finished among the league leaders with an average of 19.4 points per game. He played one more year in the BAA and finished his pro career with the Paterson Crescents of the second-tier American Basketball League.

After retiring from basketball, Sadowski lived in Bloomfield and worked in New York. He kept a summer home at the shore and owned Big Ed’s Soda Mart in Brielle during the 1960s. Sadowski was inducted into Seton Hall’s Hall of Fame in 1974 and passed away in Wall Township at the age of 75.

TRENTON’S WINTER OF LOVE

Bob Love, the future NBA All-Star, was drafted by the Cincinnati Royals in 1965 but was cut in training camp. He had the skills, but the Royals felt he didn’t have the body to survive playing forward in the pros. Cincinnati’s loss was Trenton’s gain, as Love signed to play with the Colonials of the Eastern Basketball League for the 1965–66 season. He made $50 a game and lived out of a room at the YMCA. Eastern League players worked regular jobs during the week and Love found a position at a nearby hospital as the tallest dietary intern in history.

The Colonials played games on weekends and those games could get rough. Love shared front-line duties with Walter Dukes and learned how to hold his own against beefier opponents. George Lehmann, a great outside shooter, helped stretch enemy defenses. Trenton was a handful. Love averaged over 22 points and 15 rebounds a game and was an easy choice for Rookie of the Year. Trenton battled Wilmington down to the wire before finishing second. Love returned to the Royals the following fall and made the team, and went on to become a star on the Chicago Bulls.

THE TWO MOES

During the late-1930s, pro basketball was beginning to regain its footing after being decimated by the Great Depression. Industrial leagues were beginning to flourish, with the strongest company teams providing a foundation for the National Basketball League—a very early forerunner of the NBA. The American Basketball League reformulated and the Metropolitan Basketball League, both in the New York region, kept pro hoops alive playing to small but enthusiastic crowds. From 1936 to 1939, some of the best basketball being played in America could be seen in the Hudson County town of North Bergen, thanks to the Jersey Reds.

The Reds had originally started as a Union City team. In 1932–33, they reached the finals of the Metropolitan League. A few months later, they joined the ABL and then moved up Bergenline Avenue to North Bergen for the 1934–35 season. In 1936–37, they played the Philadelphia SPHAs for the ABL championship—but lost Game 7 in overtime.

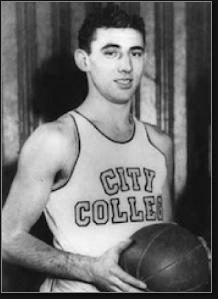

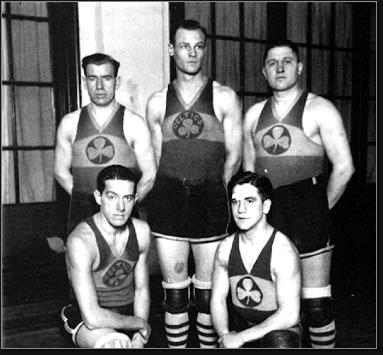

The star of the Reds was Moe Spahn (right), an All-American under Nat Holman at CCNY. Spahn was a nightmare to guard. He had an accurate set shot but could also drive to the basket with either hand if a defender tried to close the gap on him. Stationed at forward, he was adept at finishing fast breaks and was among the league leaders in scoring every place he played during his career. The Reds’ other star was Moe Frankel (left), who was less flashy than Spahn, but was a shutdown defender and a clutch shooter. A third star, local legend Hook Andersen, gave the team a legitimate triple-threat.

In 1937–38, the “Two Moes” finished among the ABL’s Top 10 scorers and led the Reds to the first-half title. They finished second in the second half. The best-of-seven league championship series pitted the Reds against the New York Jewels, an itinerant club that scheduled its home games for the series at Arcadia Hall in Brooklyn. During the regular season, the Reds and Jewels played 10 times and won five games apiece. The Jewels had a star-studded roster than included player-coach Honey Russell, Matty Begovich, Mac Kinsbrunner, Lou Spindell and Jake Pelkington. ABL games in 1938 were three-period affairs, mimicking hockey as opposed to college hoops.

The Reds won two of the first three games, setting up a contentious Game Four in Brooklyn. Pushing and shoving led to fistfights and, at one point, the Reds walked off the floor after the referee disallowed one of their baskets. ABL president Johnny O’Brien had to talk the Jersey players back onto the court. They won 56–42 to take a commanding series lead.

The Reds were especially tough on their homecourt, so it was considered a great upset when the Jewels went to North Bergen and won Game 5. However, Jersey closed out the series in Brooklyn, 30–28. The Jewels actually led 20–18 heading into the final stanza, but ice-cold shooting (Kinsbrunner went 0-for-18 in the game) doomed them to a two-point loss.

In 1938–39, Jersey made it to their third straight ABL final, but the Jewels exacted revenge by sweeping the Reds. In 1940, the two actually clubs merged rosters and made New York their official home base.

BEASTS OF THE EAST

In the spring of 1964, the cities of Trenton and Camden squared off in a best-of-three series to decide the championship of the Eastern Professional Basketball League. Trenton, coached by Stan Novak, had three of the circuit’s Top 10 scorers: New York playground legend Stacey Arceneaux (right), 6’10”rookie Jim Hadnot and Holy Cross All-Star George Blaney, all of whom averaged over 20 points a game. The Colonials also had a strong bench, featuring Cleo Hill. The big gun heading into the series, however, was Camden’s Paul Arizin, a longtime Philadelphia Warrior who chose to remain in Philly after the franchise moved to San Francisco. The burly, 35-year-old forward averaged 25.8 point per game. The Bullets also had veteran guard Hal Lear.

The star of Game One turned out to be a little-known Bullets benchwarmer named Bill Burwell. The 6’8″ reserve, who’d had a solid career at Illinois University, helped turn a slim halftime lead into a comfortable double-digit margin by the end of the third period, nailing six straight shots. Burwell’s timing was perfect, as Arizin (left) went ice-cold. Burwell poured in 20 points and collected a dozen rebounds as Camden cruised to a 131–125 victory. Lear was the high man for the Bullets with 29 and Herb Gray played shutdown defense on Arceneaux in the second half. Hadnot was the game’s top scorer with 30 points. After the final buzzer, Burwell received a standing ovation from Camden fans.

Throughout the game, a small but vocal contingent of Trenton fans gave Novak an earful—questioning everything from his judgment to his manhood during the high-scoring contest. Novak had been in the Eastern League as a player and coach since the early 1950s. Their beef with Novak dated back to the beginning of the year, when he cut a popular player named Willie Choice. Afterwards, Novak felt he had heard enough from the fans and informed GM Hal Simon that he was quitting—in the middle of a championship series!

Simon ended up taking the coaching reins for Game Two.

Prior to that game, Camden’s coach, Buddy Donnelley, was almost a no-show, too. He had to accompany his wife to the hospital for an operation, but he made it to the Trenton gym in time for the opening tap.

The Bullets won the championship in Trenton with another high-scoring performance, 142–138. Arizin got back on track with 29 points to lead Camden, while Hadnot was the contest’s top scorer again with 32 points. Burwell was great again for the Bullets, with a season-high 23 points. Another sub, Jay Norman, made a couple of clutch plays down the stretch. In the final minutes, with Arizin fouled out, Lear made two steals to blunt a final Trenton comeback.

“I feel great right now,” Arizin told reporters after the game. “Possibly the only feeling that compares with is was back in 1956 with the Warriors and we won the NBA championship. It’s a great feeling.”

Each winning player received a check for $800.

THANK YOU, SOCCER…WE’LL PASS

During basketball’s first full year, 1892, the game took off faster than anyone could make up a coherent set of rules. James Naismith, the game’s inventor, had created a brief list of instructions, which left a lot of room for interpretation. Anywhere between 10 and 20 players might take the court at the same time, and there was basically zero offensive strategy—which meant many contests were just an endless scrum for possession of the ball. In various places where the new game was played, rules were concocted to bring a sense of order to the competition, including limiting players to zones marked off on the court. A player leaving his zone would be whistled for a foul.

It took a pair of soccer players in Trenton to open up basketball. In 1893, Al Bratton and Fred Cooper (right) started playing basketball and instantly recognized that the planned, methodical passing they did with their feet on grass could be accomplished with their hands on the hardwood. At first, they simply passed to each other, sending a cartoonish mob of defenders scrambling back and forth as they worked the ball closer and closer to the basket.

Soon, their Trenton YMCA teammates joined in the playmaking; the game opened up, the pace quickened, and scoring soared. The Trenton team was recognized as the most advanced in the country, and fans came out in droves to watch Cooper, Bratton & Co. play. In early 1894, the Trenton Y vanquished the undefeated 23rd St. YMCA team from New York to claim the “world” championship. Other names on the Trenton roster included Pop Brower, Sid Smith, Charlie Hodge, Harry Bates, Will Fenton and W.J. Davidson. Cooper designed the team’s uniform, which included tights and velvet shorts.

DODGING BULLETS

The Trenton Tigers are listed as the champions of the American Basketball League for the 1946-47 season. They were indeed the last team standing in the playoffs that spring, but their title probably deserves an asterisk. It certainly begs an explanation.

The 1946–47 campaign was a wild one for pro basketball. The decade-old National Basketball League fielded 12 teams and crowned the Chicago American Gears as its champion. The newly formed Basketball Association of America struggled through its inaugural campaign with a lack of big-name players and—with the exception of the New York Knicks and Philadelphia Warriors—a ton of empty seats. The Warriors won the first BAA title but, shortly thereafter, four of the league’s 11 teams folded. The American Basketball League, four years older than the NBL but considered a notch below, fielded 10 clubs in the fall of 1946, including five in New Jersey. The ABL struggled to compete and two clubs didn’t make it to the end of the schedule.

The Trenton Tigers survived, thanks to the talents of Chilly Edelstein, Eddie Boyle (left) and Al Schneider. They had a well-balanced team that included future NBA referee Norm Drucker. The Tigers finished the year with a sub-.500 record, but still qualified for the postseason. They prevailed in their opening playoff round, defeating the Elizabeth Braves. The Tigers then upset the Philadelphia SPHAs in a best-of-three series to earn a berth in the ABL finals, winning the deciding game, 48–46.

On the other side of the ABL draw were the powerhouse Baltimore Bullets, led by future Hall of Famer Buddy Jeannette and high-scoring Mike Bloom. The Bullets cruised through their series with the Brooklyn Gothams to reach the finals.

The ABL championship series happened to coincide with the World Professional Basketball Tournament, which played to packed houses in Chicago Stadium. The Bullets calculated that their cut of the gate—particularly if they made it out of the first round of the Chicago tournament—would dwarf their earnings from the ABL finals. So Jeannette and his crew boarded a train to the Windy City and never looked back!

The Tigers rightfully claimed the league championship without breaking a sweat—literally. They were awarded the title by forfeit. As for the Bullets, they drew the Tri-Cities Blackhawks (distant forerunner of the Atlanta Hawks) and fell, 57–46.

The following season, the Trenton Tigers went 17–15 but lost in the opening round of the playoffs. They continued to play winning basketball until the team folded during the 1949–50 season.

SAND PIPE DREAM

Six decades before Donald Trump left his impetuous imprint on Atlantic City, a newspaperman named Marvin Riley (right) fired every member of a future Hall of Fame basketball team.

The year was 1922, the bootleg liquor flowed freely along the Jersey Shore, and professional basketball was still in its freewheeling wildcat days. The unquestioned class of the hoops universe were the New York Celtics—a team owned by entrepreneur Jim Furey that featured such immortals as Nat Holman, Joe Lapchick, Benny Borgmann, Honey Russell, Barney Sedran and Tom Barlow. In Ferbuary, the Celtics decided to jump from the Metropolitan League (where they were 12–0) to the Eastern League, which promised better competition and fatter revenues.

To do so, the Celtics had to swap uniforms and become the Atlantic City Sandpipers. The owners of the Sandpipers agreed to pay Furey and his players $900 a week, with Furey pocketing $300 and the remaining two-thirds split between the players. The Celtics/Sandpipers played their home games in an arena at the famous Steel Pier. As expected, they continued rolling over the competition. But to the chagrin of their new owners, the more the team won, the fewer tickets they sold. Go figure: Atlantic City tourists wanted close, exciting games, not blowouts.

After three weeks, just before Christmas, the Sandpipers were sold to the aforementioned Marvin Riley. Riley’s present to his new team was a salary hit from $900 a week to $400. The players refused to take the paycut. So Riley fired the entire team!

Riley was no basketball neophyte. On the contrary, he was among the individuals who brought the game to the Garden State in 1892. A Trenton newspaper writer, he spent the next quarter-century moonlighting as a highly respected referee—often for a percentage of the gate—and so, on many nights, pocketed as much from officiating games as writing about them.

Riley knew where to dig up local talent. He hired new players for the Sandpipers and announced that he would coach the club himself. After three games (all losses), Riley saw the folly of his scheme and gave up, folding the Sandpipers. The Eastern League itself limped through the first two weeks of 1923 before disbanding.

As for the Celtics, they became a barnstorming club after that. Their record for 1922-23—including the stints in the Metropolitan and Eastern Leagues—was 193–11, with one game declared a tie. Furey estimated that his club performed for close to a million people that season—including a crowd of 23,000 in Cleveland. The Celtics would go on to revolutionize team play and bridge the pioneer and modern eras of basketball.

YOU’RE FIRED!

The 2006–07 season marked a landmark effort by the Rutgers women’s basketball team. Vivian Stringer’s squad of tough and talented players made it all the way to the NCAA championship game. Their dream season ended with a 13-point loss to Tennessee, but the real nightmare didn’t begin until the morning after.

During his top-rated CBS morning radio show—which was simulcast on MSNBC—Don Imus and sidekick Bernard McGuirk engaged in some goofy banter that quickly crossed the line:

Imus: That’s some rough girls from Rutgers. Man, they got tattoos and…

McGuirk: Some hard-core ho’s.

Imus: That’s some nappy-headed ho’s there. I’m gonna tell you that now, man, that’s some…woo. And the girls from Tennessee, they all look cute, you know…

The blowback was immediate. Junior Essence Carson, a Paterson schoolgirl legend, said that Imus had “stolen a moment of pure grace from us. “

“I would like to express our team’s great hurt, anger and disgust toward the words of Mr. Don Imus,” she stated. “We are highly angered at his remarks but deeply saddened with the racial characterization they entailed.”

“Our moment was taken away,” added Heather Zurich. “Our moment to celebrate our success, our moment to realize how far we had come, both on and off the court, as young women. We were stripped of this moment by degrading comments…”

“I achieve a lot,” said Kia Vaughn. “Unless they have given this name of ho a new definition, then that is not what I am.”

Stringer said it best: “Let me put a human face on this…these young ladies are valedictorians of their class, future doctors, musical prodigies and, yes, even Girl Scouts. They are all young ladies of class. They are distinctive, articulate.”

CBS suspended Imus for two weeks immediately after the incident, but as the uproar over his comments grew, the network eventually fired him.

His time slot on MSNBC eventually went to Morning Joe.

TALE OF TWO CITIES

Kingston, NY, and Paterson, NJ, are about 90 miles apart and, in most respects, could not be more different. However, in the spring of 1923, the two cities most definitely had something in common. Both were hotbeds of early pro basketball—Kingston in the Hudson Valley and Paterson in the industrial heartland of northern New Jersey. The Kingston Colonials basketball team, assembled and coached by Pop Morganweck, claimed the World Championship of basketball for 1923 by virtue of their 4–2 record against the New York Celtics that season.

Fans of the Paterson Legionaries rightfully felt that their team was every bit as good as the Colonials. In fact, man-for-man, no team in all of basketball matched up better with Kingston.

That’s because the two teams were one in the same. Morganweck’s Colonials played a couple of games a week against teams in the New York State League and then switched into Paterson uniforms for an additional two games a week in the Metropolitan Basketball League. Kingston won both halves of the NYSL split season and Paterson took the second-half title in the MBL. The Legionaries benefitted from the departure of the New York Celtics, who were undefeated in the first half and then left the league to play in Atlantic City as the Sandpipers (see above).

Paterson beat the Elizabeth club (which held the second-best first-half record) for the Metropolitan championship on April 18th and Kingston took the New York State crown by virtue of their winning both halves of the 1922–23 season.

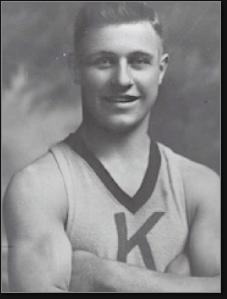

Morganweck, a New Jersey native who had been involved in pro basketball from its earliest beginnings, assembled an all-star squad, which was enjoyed by fans unknowingly rooting for the same home team more than two hours apart. Benny Borgmann (above left), the 24-year-old scoring sensation, brought crowds to their feet in two towns, along with a pair of six-footers, Harry Knoblauch and Charlie Powers.

There were some differences in the rosters, and in truth those difference probably made Kingston a shade better. The Colonials got a nice year out of 20-year-old Carl Husta and veteran Babe Artus. Gil Schwab, a tough, versatile 30-year-old, did his playing exclusively in Paterson.